By David Abel | Globe Staff | 12/28/2002

Nearly every day, the big man wanders around the city. In an old Peruvian poncho and knit New England Patriots hat, he drops in at T stations, climbs through trash in back alleys, and stops to chat up everyone from boozers to paupers.

Like many of his bedraggled friends, he has been sneered at in hotel lobbies, shooed from restaurants, and forced into the cold from train stations.

Even Jim Greene's grandmother has taken him for a homeless man.

"It doesn't bother me," he says. "It's like Dorothy Day once said in quoting Thomas Aquinas: We tend to look like those we love."

For a decade, the 39-year-old outreach worker has been the closest thing to a guardian angel for many of the city's homeless. Not only does he know nearly all their names, he has accompanied them to hospitals and appointments to see social workers, he has coaxed countless numbers off the streets and found housing for hundreds. And when someone dies, it's usually Greene whom city coroners call to identify the body.

In the past few weeks, years after helping design and maintain the city's safety nets, Greene has been apologizing to scores of men and women who have come to know him so well. Gently, after asking about their hurt leg or their medicine or where they slept the previous night, he delivers the bad news: He's moving on.

Yesterday, Greene spent his last day on the streets as an outreach worker, and next month he starts a new job at City Hall.

"It's a huge loss," says Lyndia Downie, his former boss and president of Pine Street Inn, describing his rapport with the homeless as "gentle, but at the same time urgent."

"But the good news is that he's not leaving the field, and he'll be able to continue his work at the policy level," she says.

Word of Greene's departure has spread quickly on the streets. Though he'll continue as a homeless advocate at the city's Emergency Shelter Commission, some resent his departure and feel like he's abandoning them.

"He's letting a lot of people down," says Mike Diamantopoulos, 50, a former painter who for years has lived on the streets around Downtown Crossing. "Maybe his job now has too much responsibility, or he's getting a better-paying position. It just feels like he's putting himself before other people."

Nothing could be further from the truth, Greene says.

"I'm in this struggle for the long haul," he says.

The son of a large working-class

family from New Hampshire, he spent his high school years helping build homes for the needy, his college years working in soup kitchens, and the years since earning a meager salary at homeless shelters. For him, he says, saying goodbye is the hardest thing he could do.

family from New Hampshire, he spent his high school years helping build homes for the needy, his college years working in soup kitchens, and the years since earning a meager salary at homeless shelters. For him, he says, saying goodbye is the hardest thing he could do.Of course, any goodbye is relative. Even though his new job won't allow him the same kind of time on the streets, he vows to keep checking on people and working for them in a different way.

"For me, this is a lifelong commitment," says Greene, who hopes in his new desk job to push for more affordable housing and more resources for the city's estimated 6,000 homeless.

Moreover, he notes, there are now many other outreach workers available to take his place. When Greene started in 1993, he was a "lone ranger" who prowled the streets and in a six-month period learned the names of 750 homeless people.

Now, after years of pushing city shelters to boost their outreach, there are dozens of well-trained homeless advocates who know the territory.

One is Cheryl Kane, a nurse with the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, who has worked beside Greene for years. "I've learned a phenomenal amount from him," she says.

"Jim doesn't just know everyone's name, he knows everyone's stories, and that's not easy to replace."

He's also served as a kind of unofficial liaison between the homeless, police, and local merchants, many of whom have grown impatient as the city's homeless population has doubled in the past decade.

Not bothering to change from his street garb, Greene has lobbied city officials, and beseeched everyone from officers to security guards to empathize with the homeless, rather than immediately forcing them from a warm place.

"He brings a lot to an enormous problem, what police often don't have the tools for," says Captain Bernard O'Rourke, the Boston Police Department's downtown district commander.

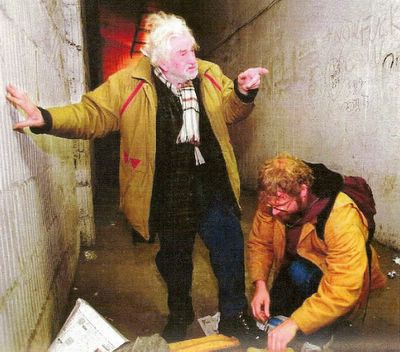

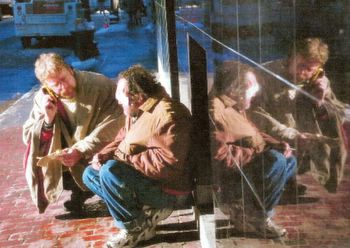

On a recent night, with the wind howling and the temperatures well below freezing, Greene follows a familiar route, checking on a panhandler named James near South Station, a scruffy elderly man named George ambling around aimlessly with a large suitcase, and a group of men guzzling alocohol in an MBTA station.

Before police come to clear the men from the station, one of whom is passed out near an escalator, and before he helps arrange beds for them at a detox shelter, he breaks the bad news.

One of the men, Rene Bouteillie, opens his reddened eyes and shakes his head. "You've always found us," he says. "You've always been there for us."

Then a man with an eye patch, Teddy Sotomayor, whom Greene has known since he started the job, staggers up from the train platform, trailed by an MBTA police officer.

Greene tries to intervene, asking the officer to let the drunken man remain inside while he calls for a van to take him to a shelter. But the officer won't relent, and the group, including Greene, is forced into the cold night.

"This is what happens sometimes," he says. "This is how a social problem becomes a medical crisis."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe