By David Abel | Globe Staff | 5/04/2003

The snoring starts as soon as the lights go out. When the bus leaves its corner, most conk out, knowing well after so many trips that this is likely to be two of only four hours of sleep tonight.

For some passengers on the late bus to Mohegan Sun, the rigid seats in tight rows aren't just beds for the night, they're the closest thing they have to a home.

Some on the packed tour bus are sojourners for a night of gambling, others are high-rolling addicts who often make the all-night trip to the enormous casino in Uncasville, Conn. But for a few like Assaad Lahoot, who rides the bus nearly every night, there's a different attraction than the "legendary gaming experience" advertised.

Most of all, the lure is shelter. Other perks: the free food and drinks. There are also many diversions. Aside from playing slots or staring at the roulette wheel, there's the live entertainment, ways to make money (other than gambling), and, importantly, the lounge where they can sneak some sleep while pretending to watch TV.

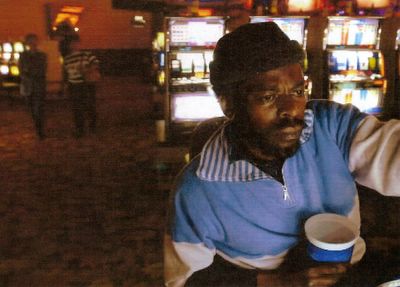

"This is my life - it's much better than sleeping on the streets or in a shelter," says Lahoot, 51, one of scores of homeless people who descend on Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods nearly every night and do their best to blend in.

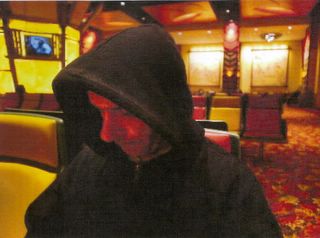

With his sweatshirt's hood pulled over his head and his body curled on the back three seats of the darkened bus, the former house painter, whose four children remain in his native Lebanon, explains how he survives:

Unable to find a painting job because of a bum arm, he says, he often spends his days standing on corners distributing a company's coupons. The little money he earns, though, is enough to afford the $10 bus ticket to the casino. After a day hanging around downtown avoiding trouble, Lahoot walks to Chinatown to catch the 9:30 p.m. bus.

In addition to the trip to the casino, the ticket comes with a $15 voucher for food or merchandise at the casino, and two $10 coupons he can use as chips for gambling. Like other drifters at the casino, if he finds a buyer, Lahoot may sell both, the voucher usually fetching $6 and the coupons $10.

The $6 profit - assuming he doesn't gamble it away - often leaves enough to tip the bus driver and ticket taker a dollar each. "It's not a bad deal," Lahoot says, adding that the benefits include an all-you-can-eat buffet.

When the bus pulls into the reservation just before midnight, it parks next to dozens of other buses from New York and New England. Some 40 crusty-eyed passengers file out. Besides Lahoot and a few other homeless men, there's a young cook hoping to win some quick cash, a mother of eight looking to "relax" after working long hours at a nursing home, a recent immigrant from Ireland on a night out with a fellow telephone operator, and a balding salesmen who says the all-night trips to the seven-year-old casino have helped send his daughter to private school.

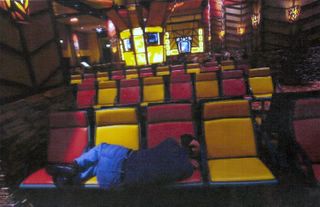

They enter the bus lounge, a brightly lit room where more than 100 vinyl red and yellow seats surround a large kiosk of several TVs. Sprawled on the seats are a mix of bedraggled visitors, some homeless, others exhausted from a day of gambling.

In the distance, through a marble hallway connecting to the 300,000 square feet of everything from blackjack to baccarat tables, are the indoor waterfalls, the 1,200-room hotel, and the plethora of high-priced shops and restaurants. Many of the regulars in the lounge, where there are only faint sounds of the incessant ringing from the thousands of slot machines, spend the whole night here - and the security guards know them well.

"They're not supposed to be sleeping," says John Barry

, one of the casino's guards who struts around the carpeted floors talking into an earpiece. "We may nudge them a bit, but as long as they wear their shoes, we let them be."

, one of the casino's guards who struts around the carpeted floors talking into an earpiece. "We may nudge them a bit, but as long as they wear their shoes, we let them be."There's John, a scruffy 40-year-old sometimes poker player who walks to the casino from Norwich, Conn., and says he's "traveling to Florida." There's Mary, an elderly Jamaican in a straw hat who spends nearly every night wandering around with a cane that she doesn't seem to use. And then there's Geri, a 58-year-old one-time resident of Las Vegas, who says she's done it all, from serving cocktails to singing as a showgirl.

Wearing large sunglasses studded with rhinestones and a black sequined dress, and with her lips painted pink, she sees a touch of glamour in her lifestyle. "Sometimes I'll spend several days here," says Geri, who like most visitors to the casino would only give her first name. "I like the ambience."

At around 3 a.m., nearly 24 hours after arriving on a bus from New York, Geri brushes on some more of the already heavy makeup, and describes her living situation this way: "You could say I'm in transition."

A few seats away, two regulars, both named George, nosh on large containers of pistachio nuts, paid for with the vouchers they received on the bus from Boston. One of them, a long-haired Asian man who says he makes his living by gambling, shows off a pricey pair of New Balance sneakers, which he bought with nearly a week's worth of vouchers. The 43-year-old dice player also shows off a pair of $200 sunglasses, which his friend bought in the same way.

Having long ago finished gambling for the night, the two Georges start arguing about whether casinos should be allowed in Massachusetts.

"People will satisfy their compulsions regardless," says the younger George, noting the thousands of jobs and millions in tax dollars a casino would bring. "Think of all the people like us. We wouldn't have to come here, and the money would stay in Massachusetts."

The other George, an 80-year-old Navy veteran and former radio operator who says he's been gambling nearly every day since serving in World War II, argues his friend's point is precisely the problem.

"I've been gambling 900 years and I know the odds are stacked against you," he tells his friend, whom he met riding the bus years ago. "It would be murder to have casinos too close to Boston. People like me would go every day - and we'd all be broke."

Not long before the bus leaves for Boston at 4:30 a.m.,

Lahoot ambles back into the bus lounge and slumps into one of the vinyl chairs. A man next to him has a jacket over his head. Another man stretches across three seats, unperturbed by the roving guards in turquoise jackets. Everywhere is the sound of snoring.

Lahoot ambles back into the bus lounge and slumps into one of the vinyl chairs. A man next to him has a jacket over his head. Another man stretches across three seats, unperturbed by the roving guards in turquoise jackets. Everywhere is the sound of snoring.Lahoot boards the bus for Boston and mumbles something about losing money while playing roulette. He shrugs and settles into the same back seat.

He closes his eyes. Dawn is breaking. Another night has passed.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe