By David Abel | Globe Staff

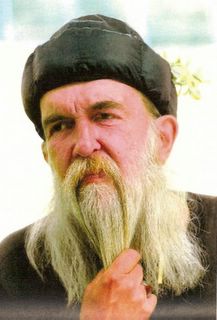

FOR MONTHS, WHENEVER I PASSED the man with the long, gray beard and tranquil smile, he would lift his eyes from one of the thick books he borrowed from the public library and greet me with a smooth Brahmin voice. It was the kind of carefully enunciated, overly proper diction you'd expect from the grand poobhas at a Cambridge faculty club than from the scruffy 60-year-old, who had grass stains covering his white pants and wore a flower in a winter cap someone had given him from Lord & Taylor.

"A good morning to you," he beamed heartily as he watched me leave my apartment building, which stood a few yards from his usual perch, an old wooden park bench beneath a large maple tree.

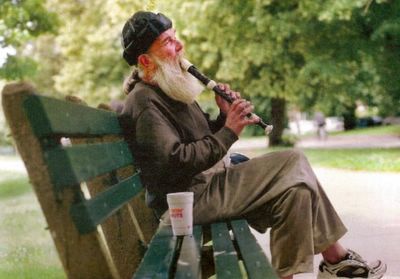

Leonard Frank Buck sat cross-legged and seemed oddly regal for a homeless man. When he wasn't reading Dostoyevsky or playing the Beatles' "All My Loving" on his recorder, he puffed his pipe and drew strangers into deep discussions, anyone from half-naked joggers to the old Russian women who attended the nearby Orthodox church, an onion-domed structure where he sometimes slept. The rosy-cheeked vagabond claimed to speak Russian, French, German, Greek, and a bit of Spanish, all of which he practiced when given the chance. "Dobroye utro," he greeted the Russians, or "Vaya con dios," go with God, he would tell the Latino ex-cons who lived at a halfway house across the street.

Leo, as he preferred to be called,

often drew me into a conversation and knew what I did for a living. After a while, he began looking for my stories in the newspaper and critiquing them, often questioning the meaning of something or regaling me with a far deeper command of the subject than I managed. The more we talked, the more I began to wonder who this bright-eyed man was and how he ended up on a wooden bench with nothing but a tattered satchel stuffed with books and a large Styrofoam Dunkin' Donuts cup, which he used to conceal the potent Steel Reserve beer he'd swig.

often drew me into a conversation and knew what I did for a living. After a while, he began looking for my stories in the newspaper and critiquing them, often questioning the meaning of something or regaling me with a far deeper command of the subject than I managed. The more we talked, the more I began to wonder who this bright-eyed man was and how he ended up on a wooden bench with nothing but a tattered satchel stuffed with books and a large Styrofoam Dunkin' Donuts cup, which he used to conceal the potent Steel Reserve beer he'd swig."This isn't as much the life that I have chosen, but the life that has chosen me," he told me one day. "I refuse to make the compromises that would change my situation. Maybe I love to suffer. Masochism has its own rewards, you know."

I had spent several years covering academia in New England, and I was usually rushing off to interview a professor or administrator of some sort at a nearby university. I had little time to ponder Leo's plight or delve into his story. In fact, he rarely gave me a chance to ask him questions. But he struck me as one of the more pensive people I'd come across, with more wisdom than many of the academics I'd met. In the few minutes we had to chat, he gently interrogated me or offered up observations about anything from relationships to religion. In some ways, and I watched it happen with more than a few of my neighbors, he had become something of a neighborhood therapist, a kind of priest without a parish.

The more I got to know him, the more the mystery of the jovial man on the bench began to gnaw at me. I wondered how someone like Leo could endure living on the streets, whether our society enabled such poverty, whether it was really his choice, whether mental illness kept him from having his own roof, or whether he was merely a man asserting his freedom to live as he wanted, unencumbered by hefty rents, a tedious job, or the gravity of owning possessions. The latter part of the deal seemed to me quite alluring. I mean, who wouldn't prefer to have no responsibilities other than having to return a novel to the library by its due date?

So, one summer morning, on a slow news day, I took a seat beside Leo and asked if he would tell me his story. It took some prodding, but after a while of hemming and hawing, he reluctantly obliged. He told me he grew up in a middle-class family in a suburb of Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he had been the valedictorian of his high school class. Afterward, he attended the University of Pennsylvania, eventually earning a master's degree in theology from the Ivy League school. Later, with the Vietnam War raging, he was accepted as a doctoral candidate at Harvard University's Divinity School.

He wasn't making it up. I called the schools to check.

The bottom didn't fall out until years after he dropped out of Harvard. "People were so uptight," he said of his two years studying at the nation's top university. "No one laughed."

Married with a son, he worked as an administrator at several area hospitals, until 1981, when superiors fired him from a job he held for seven years as a supervisor at the renowned McLean Hospital. "There was a personality conflict," he said, preferring not to get into it.

Then, in quick order, Leo's wife left with their boy. His landlord forced him out of his home. He stayed at shelters for a while, and soon after, he began living on the streets. When we met, he told me he had spent much of the previous 15 years homeless and estranged from his family.

Little could be said to glamorize Leo's life. He was one of thousands of people who lacked a home in Boston, more than a quarter of whom had a college education.

He was an alcoholic who suffered from bouts of depression and an ailment that forced him to hobble around with a cane. Over the years, he had been robbed and beaten up several times. Showering was a hassle. His meals usually came from soup kitchens, and when he stayed at a shelter, he had to be up and out by 5 a.m. To cover the cost of his tobacco and booze, he spent a few hours each day outside subway stations playing songs on his recorder, which netted him roughly $10 a shift.

But Leo wasn't the type to complain.

"The alternatives seem much worse," he told me, emphasizing that if he needed help, he knew where to get it. "I know many who are a lot less in tune with themselves."

Leo wasn't comfortable talking about himself; he preferred to learn about others, to consider their quandaries. He helped college students refine their poetry, inmates of the halfway house learn to live on the outside, and many of the local professionals, including one often-harried reporter, see a world beyond their horizons. He also liked to talk about all the friends he had made over the years - including the former Governor Michael Dukakis, whom he befriended while the erstwhile presidential candidate made his way to work picking up trash. About how, for him, there were no strangers, how he could engage just about anyone on any subject, from the spiritual roots of Hinduism to the wit of Oscar Wilde.

When a pal stopped over one morning while we chatted, Leo asked: "How's mom?"

"She's doing better," said his friend, an artist, who explained his mother had been recovering from surgery.

The two had been friends for five years. "He helps me reflect on life," the 39-year-old man told me. "We have a kind of mutual psychoanalysis. It's always interesting what he says."

A few minutes later, another old friend, a Cuban exile, stopped by to catch up. Leo asked him about his granddaughter and then the two discussed Fidel Castro for a while.

When the man shuffled off, Leo stretched out on his sturdy bench, gulped some beer from the slit in his Dunkin' Donuts cup, and then flashed his dentures with a great, satisfied smile.

We talked some more about the news, the environment, and he admired all the pretty people passing. The sun began streaming through the top leaves of the maple tree, and that meant the morning had nearly passed.

It was time to move on to the library.

Before steadying his cane and lumbering off, Leo offered me this: "There are some limitations. But it's not a bad life."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.