By David Abel | Globe Staff | 3/23/2003

Well before dawn, when howling winds cut through the thickest of winter jackets, the race begins. From homeless shelters, shanties over steam vents, or a relative's couch, they rise to tramp through the night as the city sleeps, each hoping to be first in line.

For 21-year-old Emilio Vazquez, who wakes at 1:30 a.m. to grab his place, being late might mean not buying a meal today.

In the past few years, the daily competition between the city's poorest, most desperate has intensified: More and more of the mainly homeless men, some having recently fallen from the middle class, have been gathering on corners and at storefronts around the city, scrapping to win one of a dwindling number of day jobs.

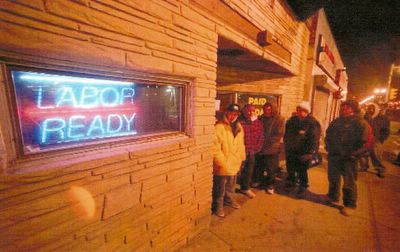

On a recent morning in South Boston, the line in front of Labor Ready's blue neon sign starts at midnight. It grows steadily, with gimpy men nearing retirement age or muscle-bound ex-cons too young to drink. Some are recently laid off with college educations; others never finished high school. There are blacks raised in Roxbury, local whites with Irish names, and a few immigrants with sketchy legal status.

They all know one thing: get here after 4:30 a.m. and forget about working today.

"The early bird gets the worm," says a 40-year-old man named Mark, who slept for three hours and then, at 2 a.m., hiked from a shelter in Uphams Corner. "Whatever people say about the homeless, I challenge anyone to say that those of us here are not some of the most determined guys you'll ever meet."

Despite discouragement by Labor Ready's local manager, who worries about sleepless workers and the predawn bustle rattling neighbors, some of the men spend the whole night guarding their place in line. And the toll can be greater than lost sleep.

A scuffle erupts every now and then. Almost all know what happened last month at a Labor Ready office in Alabama, in which a prospective worker fatally shot four other job seekers during a dispute over a CD player.

"Everyone here's on the edge," says David Fraser, 21, who caught the last train of the night from Quincy and spent the smallest hours of the morning fighting the cold with about a dozen other insufficiently dressed men. "I mean, you have to struggle - and there's never even a promise you'll get it - for backbreaking work."

And the pay? Minimum wage.

In the past few weeks, to boost the company's declining profits, Labor Ready cut the wages of nearly all its local employees from an average of about $7 to the state's $6.75 an hour minimum. Despite the pay cut, Labor Ready continues to charge companies between $12 and $18 for their work.

Not everyone, though, is eager to complain, especially when a lack of job security creates fear of being blackballed from future work.

Homeless since he ran away from

his home in Roxbury five years ago, Emilio Vazquez refuses to bicker about the work conditions. Hurrying over from the Pine Street Inn by 2:15 a.m., he holds the No. 5 spot in line, a position he prays will get him a job.

his home in Roxbury five years ago, Emilio Vazquez refuses to bicker about the work conditions. Hurrying over from the Pine Street Inn by 2:15 a.m., he holds the No. 5 spot in line, a position he prays will get him a job.Nearly every day over the past year, the brawny high-school dropout has come here looking for work, and perhaps because he's young, strong, and enthusiastic, he gets it on average four days a week. The jobs? Demolition work. Clearing construction sites. Shoveling snow. Loading or unloading trucks.

"We all know what we're getting into, and without Labor Ready, many of us probably wouldn't be able to find other work," says Vazquez, who often doesn't eat until getting paid at day's end. "Yeah, it's hard work, and it can be dangerous, but we need the money."

When the Labor Ready manager unlocks the barred door at 5:30, at least 20 men rush into a small, sterile office, signing their names on a list numbered by their spot in line. Under a sign promising "Work Today, Pay Today," they take turns filling up on the free coffee, which one man says is "so bad it gives you the runs."

Drowsy and ornery, the men settle into plastic chairs, most taking the chance to catch a few winks as others stare into the fluorescent lights. Newspapers are read and re-read, the Styrofoam cups refilled, the silence belies a palpable tension.

Some of the men worry they'll be deemed too old or too weak to work that day; others wonder if the manager sees them as too inexperienced or unstable. And there are those convinced there are favorites who will get work no matter what time they arrived.

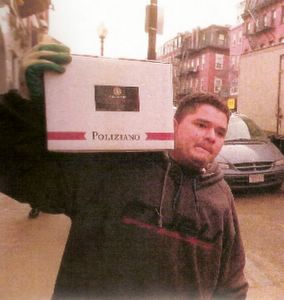

It doesn't take long for the morning's first winners to get their prize. The manager sends Vazquez, Mark, and three other men to a coveted job in Somerville, where they'll spend the day on trucks delivering boxes filled with liquor.

"The others hate us because we're getting this job," says Vazquez, noting that unlike most other day jobs, this one guarantees at least 10 hours of pay. "But this is my dream job. If they offered me a full-time position, I'd take it in a heartbeat."

Three hours later, while Vazquez and the others are well into their day of heaving heavy boxes down slick, narrow stairwells at restaurants and liquor stores throughout Boston, more than a dozen other men are still at the office in Southie, hoping against the shrinking odds for work.

Pacing the butt-strewn sidewalk, Mark Dlugosz, a 50-year-old former nurse and one of the few men with his own apartment, says he's three months behind on the rent. If he doesn't land a job today, he says he'll probably spend the rest of the day collecting cans or fishing through trash bins. And if can't find work soon, he says, he'll be sleeping at the Pine Street Inn, where he used to volunteer.

Jason Bergeron, a 22-year-old dad who lost his last job as a painter when his boss moved out of town, isn't happy about crashing on his mother's couch at her cramped apartment a few blocks off West Broadway. If he can't get a job, he says, he may turn to theft. He has called every painter in the phone book, but he can't find a job. Everyone wants to know if he has a car, which he lost after driving with a suspended license.

"Standing here doing nothing is worthless," says Bergeron, who says he needs the money not only to eat - but also to pay court fines. "I'd rather make the money than steal, but you do what you have to do to survive."

A few minutes after 9, William Criss gives up. The 51-year-old, who says he only has $2 to his name - money he hoped to use to travel to work this morning - trekked here from the Boston Rescue Mission at 3:30. A regular for several years at Labor Ready, it's the third time in the last week, he says, he hasn't landed a job. So with all his possessions, two small bags stuffed with socks, shampoo, and colored pencils, he takes off. He'll spend the day at the library drawing detailed portraits of fancy homes he'll never own. "I'm more disappointed than angry," he says. "It's been a long time since I've gone out."

Later in the day, Vazquez returns to Labor Ready to collect his pay - $61 after taxes and the fees for using the company's cash machine. His hands are blistered and his feet are swelling. Despite the cold and little more than a hooded sweatshirt to keep warm, he's been sweating all day, having made 42 deliveries.

But now, with the sun setting and some cash in his pocket, the effort feels like - as he puts it - "you didn't waste the day."

More to the point: it's now time to eat. Across the street is a Burger King, and after that, he'll take his girlfriend to a proper restaurant, as he occasionally does when he has money to spend.

"And why not?" he says. "I bust my butt all the time. I should be able to treat her, and myself, nice sometimes."

No matter what, though, it won't be a late night.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

Sidebar:

By David Abel

Labor Ready, the nation's largest day-labor provider, filled 50,000 fewer jobs last year than the year before. In Massachusetts, the firm's 22 branches last year put 13,000 people to work, 4,000 fewer than in 2000. The decline in jobs has been a blow to its bottom line, and the reason the firm recently cut wages in the Boston area.

"What it comes down to is that our wages are subject to pricing pressures," says Stacey Burke, a spokeswoman for Labor Ready, whose stock has dropped 80 percent since 1999 and whose profits have plunged in half, to $11.5 million in 2002.

Social activists and many workers, however, argue that in fact many of them end up making less than minimum wage.

For one thing, they note, the workers nearly always pay the tab to get to their jobs, which in Boston usually involves a train or bus ride. There are the hours they wait for work, which are unpaid. And then, for those lucky enough to score a job for the day, many end up collecting their wages from Labor Ready's special cash machines, which deduct as much as $1.99 from their pay.

The check-cashing fees add up: In 1999, they earned Labor Ready $7.7 million. A year later, after groups in other states filed suits against the company, the Campaign for Contingent Workers, a local nonprofit, persuaded the Massachusetts attorney general's office to order the company to cease charging fees to workers who use the cash machines.

The company's continued use of the cash machines - the attorney general's office says it's responding to complaints against Labor Ready, but officials declined comment on any possible investigation - as well as other allegations that it exploits its workers, spawned a protest movement last year in Western Massachusetts. A nonprofit group called the Anti-Displacement Project organized scores of Labor Ready workers, picketed the company's offices, and launched a website, slaverready.com, which, among other things, accuses it of "modern day slavery," "selling cheap, human labor at the lowest possible cost to its customers."

Earlier this month, the group accused Labor Ready of trying to block its organizing efforts, and it filed unfair-labor practice claims with the National Labor Relations Board in Boston.

"At a time when the social safety net has been cut, people are facing the prospect of no income and a day-labor job where people may have their rights violated on a daily basis," says Minsu Longiaru, an attorney for Greater Boston Legal Services, who has interviewed scores of Labor Ready workers who accuse the company of everything from age discrimination to unsafe working conditions. "This isn't a choice they should have to make."

The company says it maintains a "zero-tolerance policy" toward discrimination, makes safety a priority, and does its best to provide its workers with good jobs and competitive compensation. And despite the inevitable predawn race, it insists that workers whose skills fit the job are chosen, not simply those who sign in first.

As far as the cash machines go, company officials argue they're a perk for their employees, who have the option of receiving a check. Though many of the employees need the money as soon as they finish work, often at a time when most banks are closed, the officials say they're charging fees equivalent to what most banks would charge.

To counter the protests, and what they view as a defamatory website, Labor Ready, in December, filed a lawsuit in federal court against the Anti-Displacement Project, charging the group with infringing on its trademark.

"We have a responsibility to our shareholders to defend our brand, and that's all we were doing," says Burke, Labor Ready's spokeswoman. "What we all need to do now is stay focused on finding work for these people. I think everyone can agree on that."