He had no money for his escape, so she gave him everything she had. They were separated by thousands of miles, an authoritarian government, and a maze of bureaucratic obstacles in four countries, but they yearned to live together like an ordinary couple.

It had been nearly a year since the survivor of Angola's brutal civil war and the daughter of a middle-class German family last saw each other in Cuba, where they married. He used her savings to pay for the planes, buses, and horses it would take for them to meet in Boston, a city they heard welcomed immigrants.

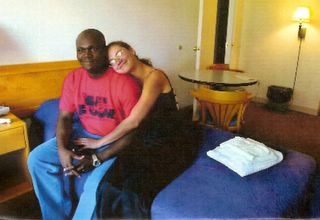

But not long after Nelson Da Costa and Maren Tober were reunited on a blustery day last fall in Copley Square, the young, penniless couple were separated once again. Without a place to stay and lacking visas to work, the two college-educated artists were homeless, forced to sleep apart in shelters that segregate men and women.

"It was horrible we couldn't live together," said Da Costa, who is seeking asylum in the United States. "That was the only reason for us to be here."

One of the few childless, married couples of the thousands of people using the city's shelters, they've spent the past eight months meeting social workers, lawyers, and city officials, hoping to find a place where they could live together.

This week, after he spent months sleeping on a cot in a Dorchester church basement and she in a cramped room at the Pine Street Inn, they're swapping the misery of homelessness for the luxury of being housekeepers.

For the next 16 weeks, they will have the use of an exclusive gym, with a sauna and Olympic-sized swimming pool included, and what amounts to their own two-bedroom apartment, with central air, cable TV, and a view of Boston Harbor.

The couple, each of whom speaks four languages,

required a unique solution to their unique predicament. One day, the city's chief homeless advocate called a hotel in Charlestown, and asked if they had a room to spare. Instead, the hotel provided two rooms, one to be use as an art studio and the other a bedroom, with a full-size kitchen.

required a unique solution to their unique predicament. One day, the city's chief homeless advocate called a hotel in Charlestown, and asked if they had a room to spare. Instead, the hotel provided two rooms, one to be use as an art studio and the other a bedroom, with a full-size kitchen.For at least the next four months, the couple will live at the hotel, which the manager asked to keep anonymous to avoid a deluge of similar requests. In return, they'll work a combined 40 hours a week, including helping to paint rooms, while housekeepers vacuum their floors and change their sheets.

"They're practically newlyweds, and it's sad a homeless shelter was their starter home," said Eliza Greenberg, the director of the city's Emergency Shelter Commission, who helped reunite the couple. "We wanted to do better by them."

It's been a long trip to find such comfort, though the consolation competes with an unease about the future.

Raised in a small village in the mountains of Angola, Da Costa, 32, watched soldiers murder his family and many of his neighbors during the country's civil war, according to a statement he wrote as part of his asylum application. An orphan, he was shot and left for dead when rebel soldiers attacked his orphanage.

A doctor from Cuba, which sent thousands of troops to support the leftist government in the war-torn African country, found Da Costa, taught him to paint, and after watching him slowly recover from the wound to his shoulder, helped him win a scholarship to study in Havana.

Tober, 24, grew up in a loving family in the formerly communist East Berlin, where teachers once spoke romantically about the Cuban revolution. An aspiring artist who studied Spanish, she decided to travel with a student group to Cuba, where the warm light of the tropics would inspire her painting.

The two met there in 1998, and almost immediately, fell in love. She visited again, and in December 2001, they were married at a small villa in Havana. But marriage to foreigners in Cuba can raise suspicions, and when Da Costa sought a visa to move to Germany, he said, the Cuban government threatened to send him back to Angola, where he feared for his life. Further complicating matters, the German Embassy told him he could only apply for a visa from his homeland.

With pressures increasing on him in Cuba - Da Costa believed he could be sent back to Angola at any time - the couple devised a plan: Tober would return home and earn some money. When she had enough, she would send him the cash needed to escape. Then the two would meet in Boston.

They arrived in Boston this past November, Tober by flying from Germany and Da Costa by a more circuitous route. Using $3,000 she wired him, Da Costa flew to Nicaragua, Belize, and then Mexico, where he followed a group of Guatemalans across the Arizona border, traveling by truck, horse, and at times on foot. From the border, he spent three days in a van before reaching Boston.

Tired and broke when they met each other outside Trinity Church, Da Costa and Tober went to a refugee center and received $20 and directions to the Pine Street Inn. Without children, the couple were not allowed in family shelters. And lacking residency, they were not entitled to public housing.

"All we want to do is be normal people, to use our education, and live together in a free country," Tober said.

Since arriving in Boston, the couple has found an attorney to press Da Costa's asylum case, improved their already proficient English, and spent as much time as possible painting, with supplies donated to city homeless programs. She paints mostly landscapes, places she dreams of going, with warm colors she says symbolizes her hope for a better future. He paints colorful collages of the faces that still haunt him from Angola, a style he calls "figurative expressionism," dreamscapes of suffering and a lust for renewal.

When not painting or working on his asylum - Tober came on a tourist visa - they've been searching for a way to live together.

This week, they finally had that chance for the first time since their wedding.

As they lugged her battered suitcases and his garbage bags filled with clothes to the hotel this week, both had trouble accepting that the spacious room with the private bathroom and the big windows was really theirs, at least for the next four months. Taking it all in, Da Costa said: "It's beautiful. It's perfect. The body is here, but the mind is still in the shelter."

Holding his hand, then hugging him, Tober said, "You see it but you don't believe it."

If they find permanent housing and obtain legal residency, De Costa said, he hopes to work teaching special-needs children, using art as therapy. Tober said she would like to start her own business, selling their paintings, and one day, opening their own gallery.

Until then, without the easy access to food at the shelters, they'll be struggling to find enough to eat.

"There are so many emotions right now," Tober said. "But this is a good start. We'll get by."David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe