When he donned the mask to the oxygen machine, the gray-haired man would be carried off somewhere, to a conscious dream state in which the pale cement walls he blankly stared at in his new home became a screen, one in which his mind projected the same scene, over and over again.

In the beginning, he kept asking himself: "All I had to do was stay in there another minute. Should I have stayed? Would I be better off dead?"

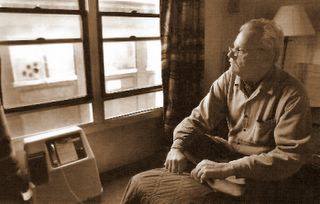

A year later, marking the slow-passing days hour by hour, one Red Sox or Celtics game at a time, he paced about his small room, wearily watching as the winter sun passed over the old abandoned factory outside his window, one sign he wasn't in hell. Purgatory, however, he couldn't rule out. Alone and eviscerated by guilt, Robert "Bobbie" Orr struggled to resist the temptation of suicide, a steady tug of a tide that threatened to consume him every day.

On Oct 28, 2002, the now-58-year-old former hospital housekeeper woke up around 4 a.m. on his living room couch, took some medicine to help him sleep through a bout of bronchitis, and lit a cigarette. Then he fell asleep. Moments later, heavy smoke and flames began ripping apart his four-bedroom house in South Boston.

Caitlin, his 8-year-old daughter, was trapped upstairs. Blind in his right eye, Orr couldn't see through the increasingly heavy smoke. He made his way to the steps. Because of severe emphysema, he hadn't climbed them in some two years, he said. He fell on the fourth one, he said, and began screaming for his daughter: "Get out! Open the door. . . . Come down to me!"

He heard her scream, too, but he couldn't make out what she was saying. Then he heard a thud Caitlin dropping to the floor.

The heavy smoke and rising flames left the frail,

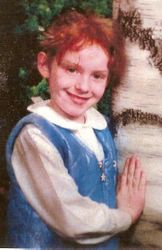

lanky man little time to think, and he did something he said he has regretted every day since. On his hands and knees, he said, Orr found his way to the front door and crawled out. A few minutes later, he witnessed a scene burned forever into the fore of his consciousness: A firefighter emerged from the second floor with his red-headed girl, her arms dangling lifelessly from the large man's grasp.

lanky man little time to think, and he did something he said he has regretted every day since. On his hands and knees, he said, Orr found his way to the front door and crawled out. A few minutes later, he witnessed a scene burned forever into the fore of his consciousness: A firefighter emerged from the second floor with his red-headed girl, her arms dangling lifelessly from the large man's grasp."My daughter's dead because of my stupidity," Orr now says. "It's something I struggle to live with every day."

The death of Orr's daughter in the house on Bowen Street made headlines for a while. Illegally parked cars, firefighters said, hampered their rescue efforts. The delayed response led the city to post tow signs on street corners throughout Boston.

The mix of intense publicity, guilt, and shame has left Orr feeling like a pariah in a neighborhood where he had lived his whole life. He rarely returns to South Boston, except for counseling appointments and visits to his bank.

Crestfallen and homeless since the fire, Orr doesn't blame his neighbors for parking improperly. "No way will I point fingers," he says. "Bottom line: The buck stops here. It's my fault. I have no ill feelings to anyone."

The same, however, can't be said for him. People still question whether he did enough to save his daughter. And, soon, he may be embroiled in a lawsuit with Robin Miller, Caitlin's mother, who this summer bought a legal ad in the South Boston Tribune announcing her intention to file a wrongful-death suit.

Miller, who left Orr in 1998 and lacked custody of Caitlin when she died, last lived in Brockton, but she recently moved out of the state, to an address she wouldn't disclose. Reached recently at a hotel in Lee, she said she feels no sympathy for her former boyfriend.

"He murdered my daughter," she said. "He could have gotten her out of the house, but he ran and he left her there to die. You want to know what anguish is? He tore my heart out, and he stomped on it. I look at pictures of my daughter every day and cry my heart out."

Asked why she wants to sue him, Miller said: "All I'm trying to do is get some justice for my daughter. She didn't deserve to die like that."

The unrelenting criticism from Miller and her family, publicized last year on television and in newspapers throughout the area, led the disabled man to seek a place to lay low, a refuge that would provide him some space from all the scrutiny.

At first, he stayed at the South Bay Holiday Inn, but the Red Cross would only cover the unemployed man's expenses for a few days, requiring him to shell out $140 a night. Not long after, he learned about the Constitution Inn in Charlestown, one of the nation's few nonprofit hotels and a longtime shelter for victims of some of the area's worst fires.

It was an odd place to live for someone trying to recover from the trauma of a ravaging fire. When he saw burn victims waiting for skin grafts at Boston Shriners Hospital, it would make him think of his daughter, who had been a second-grader in the James F. Condon Elementary School. "What am I doing here?" he would ask himself. Now, after a year living with others who have lost everything in fires, he says, "It's good therapy."

Orr has two sisters in Avon, one of whom owned his house in Southie. But they have children, and there wasn't enough room for him. He applied, he says, for an apartment through Boston Public Housing. But they refused him, he says, because he's a fire risk.

For now, paying about $20 a night, he's settled in a room at the former Army Services YMCA. It's not much, but he has his own space, a refrigerator and stove, a private bathroom, and a crew who cleans his room every day.

"I'll stay here until they throw me out, or until I die," he says. "I feel safe and protected here."

His sisters, who visit him once a month or so, worry about him.

"It still hurts so bad. It's something I don't think anyone can really get over," Lorraine Robinson said of her brother's loss.

His other sister, Mildred Davis, said: "He's depressed, isolated, and his health has gone down. He still feels totally devastated."

Lifting himself up from his thin, twin mattress one recent morning, his breathing tube connected to his nose, Orr pointed out the things that keep him going.

There was his one surviving picture of Caitlin, whom he had named after his former supervisor at the New England Medical Center, where he worked for 20 years until emphysema forced him to quit in 1995. There was the figure of the Virgin Mary, which he keeps next to his daughter's picture. There was the sports talk radio, which he listens to almost nonstop. And there was the table full of medicines: for his heart, blood, eyes, throat, and lungs.

He walks slowly, rarely ventures outdoors in the cold, and coughs a lot. "It's hard to breathe," he says, clearing his throat with an inhaler.

But what most keeps him going, he says, are the memories of Caitlin: their walks in the park, the visits to the zoo, and the laughs they shared while playing with "Bear," their shepherd.

He also wants to send a message to the firefighter who did what he couldn't do. He says he never got the chance to talk to John Cetrino, who pulled Caitlin from the blaze, but he says he wants to thank him, to ask for his forgiveness.

"My daughter has given the gift of life to seven people," he says, pointing out that several parts of her body were donated to recipients. "It's through his heroic efforts that the gift of life has been given to these people."

For his part, Cetrino also has a hard time letting go of Caitlin. As if it just happened, he still feels the weight of her limp hand, which he found hanging from a sheet wrapped futilely around the girl. He still feels the heartbreak from learning that Caitlin didn't survive.

He also understands the anger, but Cetrino is willing to forgive. "An accident is an accident," he says. "I feel bad for all the parties involved. She was a beautiful little girl. But I don't hold anything against her father. He has to live with this every day, for the rest of his life."

And that's the hardest part. No matter the extent of counseling or the distance time provides from the fire, Orr struggles to make it from one day to the next, hour by slow-moving hour, breath by labored breath.

"What it comes down to right now is that I'm trying to go forward, not backward," he says.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe