By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/19/2003

The view from the porch consists mainly of a large concrete pillar, the air inside hangs heavy with exhaust fumes, and one of their neighbors, a methadone clinic, attracts scores of heroin addicts every day, but Thomas, David, and John prefer to point out the perks of living in a hut under the Southeast Expressway.

Sure, the rumbling overhead of more than a million cars a week never stops and they often awaken with sore backs, but they view the noise as background music and their beds, blankets folded neatly on the ground, as a cozy, increasingly comfortable refuge.

"For right now, this is as good as it gets," says Thomas, 47, a Roxbury native who, like others, would provide only his first name. "This is our little place and we try to keep it nice. And, right now, it's our only choice."

Beneath the expressway by Berkeley Street, the three homeless men are part of a phenomenon more common to cities in the developing world: All around them, a shantytown is rising from the detritus of the Big Dig.

Over the past few months, as the size of the city's homeless population has risen and state budget cuts have slashed hundreds of shelter beds, about 50 men and women here have built an array of huts, making roofs from old tarps, walls from loading pallets, and doors from discarded road signs.

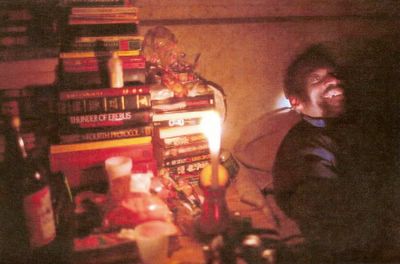

Thomas's new home includes a relatively plush throw rug he and his roommates found in a dumpster, a coffee table-sized wooden spool that displays their growing library of books - ranging from those by Hunter S. Thompson to Isaac Asimov - a fire pit where they grill shish kebab and chicken livers, and their prized possession: a pillowy couch recently donated by Big Dig construction workers.

The increasingly settled community around them includes teenage runaways, a middle-aged Native American, out-of-work Latino immigrants, blacks and whites, and one 81-year-old veteran of the Korean War.

Some fit carpeting and mattresses between abandoned iron beams left from the construction. Others use blankets and cardboard to insulate the large funnels that molded the expressway's concrete pillars. One man pitched a tent, and others make do with little more than a pile of blankets and the elevated highway as a roof.

"We're hearing more and more of these stories, but an encampment in Boston is something new," says Ed Cameron, deputy director of the Emergency Shelter Commission of Boston. "This is a frightening sign of where we're heading. Many of these people really have no other place to go. There's just no room for them. So, the police often look the other way. They have nowhere else to take them."

There are no current numbers for the size of the city's homeless population. A census one night last December found about 6,000 people in shelters and on the streets.

But since then, shelters report more and more people are vying for fewer beds - this summer the state Legislature cut funding for 328 beds - and state officials say record numbers of families are turning up in government offices seeking shelter. Part of a nationwide rise in homelessness, the surging local numbers foretell a crisis this winter, city officials and social workers say.

"I usually say it goes up gradually, but this year it's stunning," says Dr. James O'Connell, who, as president of Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, keeps a close watch on the city's homeless population. "There are just more people now than we can cope with this winter."

Like others below the expressway, many of whom have been living on the streets for years, Thomas, David, and John are well aware there aren't enough beds. So, they've decided to winterize. With the few dollars that Thomas and John earn from demolition work and about $100 a week David pulls in panhandling, or "stemming," as he calls it, the roommates have bought a battery-powered halogen lamp and they're planning to buy a generator and a propane burner to help keep the place a bit warmer.

While they prefer their hut to the crowded shelters, they're conscious of the dangers of living outside. There are numerous thefts and assaults, and in the winter the area beneath the highway becomes a wind tunnel. In recent years, several homeless people died sleeping there.

"My biggest fear is that someone will sneak up on us at night," says David, 33, a Dorchester native who says he has earned as much as $135 panhandling in one day. "I'm not so worried about the winter, as much as staying safe. We try to keep it quiet."

Others, however, are angry there's no room for them at shelters, especially the Pine Street Inn, which has been full every night for much of the past two years. Just a block away, the shelter, the city's largest, has yet to open its lobby, where as many as 200 people slept last winter.

Another homeless man named David, who works as a cook, has suffered turf battles over an insulated funnel where he and a few others regularly sleep. The 37-year-old father, who says he can't afford an apartment because most of his money goes to paying child support, is sick of the fights, the thefts, and the cold. If he could get a bed, he says, he would much prefer to sleep at the shelter.

"It's completely crazy," he says. "Pine Street has space in the lobby - why don't they open it up for us? I'd sleep on a bench there, if they'd let me. It would be much safer."

Pine Street officials say they would like to do more, but they blame the Legislature, which cut the state's budget for homeless services from $37 million in fiscal 2002 to $30 million in fiscal 2003. The cuts, they say, mean the shelter has less money to pay for staff, meals, and counselors to serve the hundreds who seek beds there every night.

With winter approaching, Pine Street president Lyndia Downie says: "We're extremely worried . . . It will exacerbate an already dangerous situation. Right now, it feels like we're trying to plug a dam."

Despite the dangers of sleeping outside, many of the squatters here insist they're relatively well off, at least compared with other homeless people.

At 22, after running away from home four years ago, Laurie boasts about her "hootch" below the highway, a sizeable wood-framed shack covered in plastic. She likes it because she can stay with her boyfriend, make her own rules, and wake up whenever she wants. Also: There's no rent.

"It's the life," she says. "No one bothers you."

There are other perks: Many of the Big Dig workers look after the homeless here. Of more than a dozen homeless people interviewed, almost all had a story of a construction worker bringing them food, offering them wood, buying them lunch, bringing them mattresses, and even offering them jobs for the day.

Sitting in a chair at a table he built from an old cable spool, Robert, the 81-year-old Korean War vet, can't say enough about the kindness of the large men in hard hats. With a small painting of fruit and wine hanging behind him on a rusting iron beam, he holds a container of low-fat cottage cheese, points to boxes of doughnuts, and then gestures at a full-sized futon. All of them, he says, were gifts from Big Dig workers. "They're very nice," he says.

Though the homeless are sometimes viewed as a nuisance - particularly when they're found passed out beneath flatbed trucks or other equipment scattered under the expressway - Big Dig workers seem to have a grudging admiration for them.

Many have stories about the homeless, whom some have come to know well. Others praise their ingenuity.

"They make use of whatever they can get their hands on," said Mark Sarracco, an electrician who sees the homeless every workday. "They really can be quite creative."

Life under the highway has become routine for Thomas, David, and John, who after several months here have perhaps the most elaborate setup in the new neighborhood. They play solitaire at night and wake up to the sound of the same large truck that hurtles by around 4:30 every morning.

"It's our alarm clock," says Thomas, a graying, muscular African-American who speaks Spanish fluently and favors books by Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson.

At dawn, before he and John head off to find work, they make their beds, tidy the place up, and pour some charcoal in the fire pit to cook breakfast and lunch. David gets up later, tames his scruffy red beard, and watches over the hut. Ambling along nearby roads, he carries a cardboard sign that reads: "Homeless. Hungry. Please Help. Thank you."

The three men met on the streets several years ago and have been looking out for each other since.

"This is our life," Thomas says, getting a nod from David. "It could be worse."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Follow:

SHELTER IS MAKESHIFT, INDEPENDENT

By David Abel

1/19/2003

A crust of ice covers the Charles. Mounds of frozen snow have reshaped the cityscape. And now, deep in the dead of winter, rarely a night passes without the temperature tipping into the teens, or below.

But they're still there, still refusing to compete for a bed at one of the area's crowded shelters, still thankful when they wake up every morning that they're alive and able to hear the drone of traffic passing overhead.

The score of stubborn homeless men and women who built a small shantytown beneath the Southeast Expressway last summer haven't budged since. A fire they made to keep warm destroyed one hovel, and Big Dig construction has hemmed them into a smaller area. But they have used everything from leftover pallets to discarded road signs to reinforce their makeshift huts into what they increasingly view as permanent homes.

"This is our solution to the lack of affordable housing," said Hung Chin, 42, a cheery former sushi chef who braves the winter nights in an elaborately constructed hut with two older men he calls "his fathers." "For as long as I can see, this is our home," Chin said.

Police, city officials, and outreach workers are all well aware of the encampment, a cluster of wood structures and tents just south of East Berkeley Street. Despite repeated efforts to persuade them to come indoors, most of the homeless insist they're better off out here than in shelters, where they would have to abide by rules. They also say they worry about being in close quarters with hundreds of other impoverished, often inebriated people.

"As long as they're not trespassing and it's not a health and safety issue, we're tolerant of them," said Sergeant Tom Lema, who handles homeless issues for the Boston Police Department.

And though city officials see shelters as a safer option than sleeping outside, they won't force their views on them.

"While we're concerned about their safety," said Eliza Greenberg, director of the city's Emergency Shelter Commission, "we respect their autonomy."

Despite the constant howling of frigid winds, which cut through the thin walls of their hovel, Chin and his housemates, Paul Savard, a 60-year-old former line cook, and Bob Gurney, an 83-year-old Korean War veteran, said they were content. Pouring diesel in a glass jar to fuel a small flame, Chin, a Vietnamese immigrant, showed off his homey decor, much of it donated by Big Dig workers.

There was the carpet on the floor, the alcoves where they put their mattresses and store their canned food, and a sturdy chair by the entrance for visitors. The walls and six-foot ceiling are lined with planks of wood, ratty wool blankets, and everything from old scarves to mattresses that block wind. By the road sign, which serves as their door, there was a makeshift armoire, which features a collection of old trophies, matchbox cars, watches, and glass trinkets they have fished from trash bins.

"It isn't so bad," said Gurney, who was barely visible on a recent night beneath a half-dozen heavy blankets. "It could be much warmer, though."

To ward off the cold, their neighbors have taken some creative, if risky, measures. While some have bought, stolen, or found fiberglass insulation, which they have stuffed between their wood and blanket-covered walls, others rely on propane burners or large cans filled with wax.

Between beers, three longtime roommates who only gave their first names - David, John, and Thomas - took turns holding their hands to several candles melted on a wobbly table. In the same frayed sweater and ripped jeans he has worn for months now, David, 33, who once helped shoo a raccoon from John's bed, explained how their previous place burned to the ground, charring a portion of one of the new expressway's concrete pillars.

"We lit a fire, and no one put it out," he said, emphasizing that they have been more careful since then.

Next door, Laurie and her boyfriend, whose porch has a welcome mat and some shrubs arranged for ambience, insisted that they were more vigilant. Though they keep their place warm with candles and a gas grill, which they also cook with, they have taken precautions, mounting a battery-powered fire alarm and an extinguisher inside.

"We're not taking chances," said Laurie, 22, who abandoned her previous "hootch," a less-spacious structure insulated by little more than a plastic tarp.

Some residents are eager for better accommodations. Sleeping alone one morning in his hovel, which is below freezing despite carefully installed fiberglass insulation, a 33-year-old day laborer named Jimmy peeked out his door and complained, "It's cold."

Dressed in two layers of clothing and wrapped in five heavy blankets, he said he never expected to still be there when he first built his hut three months ago. He occasionally spends the night at city shelters. Now, living off sandwiches donated by outreach workers and a local church, he said he was trying to save up to afford his own apartment.

Some nights, he decides to stay at the Pine Street Inn, which is a block away, across Albany Street.

"It may not be ideal in here, and we're the first to admit we're overcrowded," said Shepley Metcalf, a spokeswoman for the Pine Street Inn, which recently crammed 160 extra people into its emergency shelter. "But they have to understand it can be dangerous to be outside this time of year, especially when they're making fires."

For Hung Chin, the danger is relative. With his two roommates, enough food and alcohol, and the heavy jacket and ski mask he now rarely takes off, he said: "You learn to live with the cold."

Showing off the strength of his walls, which Big Dig workers built, and pointing out the special touches, including a frozen pineapple resting on a cinderblock and stuffed animals hanging from the ceiling, Chin said he and his roommates are here to stay.

"We have nowhere else to go," he said. "This is our own place, and we'll keep it as long as we can."

Follow:

BOB GURNEY, 72; VETERAN

By David Abel

Globe Staff

1/26/2003

He was a father, an accomplished electrician, and a veteran of the Army who served two tours during the Korean War.

But something happened, and years ago, Bob Gurney disappeared.

"It was like the earth swallowed him," said Denise Perkins, his niece and one of only two surviving relatives.

On Tuesday, emergency medical workers found the 72-year-old longtime South End resident dead in a dilapidated hut where he was living with two other homeless men.

Perkins said she and her brother had spent years searching veterans hospitals and records of vital statistics for any sign their uncle was alive. The youngest of four in a working-class family, Mr. Gurney last saw his niece and nephew at his brother Paul's funeral some 30 years ago.

After learning about his death from news reports, Perkins said: "It grieves me deeply. We could have done something for him if we knew where he was. Family is very important to us and he was very important to us. This is really a tragedy."

Mr. Gurney grew up in the Mission Hill housing development. One of his oldest friends, retired Boston police officer John Sacco, who attended the former Boston Trade School with him, described Mr. Gurney last week as a "bright, hard-working guy."

The two used to play penny-ante poker and take drives in Mr. Gurney's jalopy. The son of a junkyard owner, Mr. Gurney was the only one of his friends to own a car, Sacco said.

After graduating from trade school, where Mr. Gurney studied to become an electrician, he took a job with the city repairing damaged traffic lights, Sacco said. Afterward, in the 1950s, he joined the Army and served in Japan during the Korean War.

"He used to regale us with stories about Japan," Sacco said.

When he returned to Boston, he found a place in a rooming house in the South End. Mr. Gurney took a job unloading lumber from freight trains, and once, when Sacco was looking for extra cash, he brought along his friend to work with him.

"I quit after the first day," Sacco said. "The work was brutal, but Bob was physically strong and hard working."

At some point, Mr. Gurney met a woman and they had a child. The two never married.

Mr. Gurney was apparently close to the boy, who died about a decade ago, Sacco said, adding that he didn't know the son's name. Outreach workers who later came to know Mr. Gurney said he often spoke about his son.

Jim Greene, a former outreach worker with the Pine Street Inn, said he often heard Mr. Gurney lament, "What sense does it make that I lived and my son died?"

About a year ago, according to Greene, now an official at the city's Emergency Shelter Commission, Mr. Gurney was forced out of an apartment on Shawmut Avenue, where he had lived for the last three decades. The landlord renovated the building, rents went up, and he was evicted, Greene said.

For a while, Mr. Gurney spent his nights at the Pine Street Inn. Doctors who tried to treat him there said he always refused help.

Sometime this summer, Mr. Gurney, who by this time whiled away most days drinking, took to living under the Southeast Expressway with two younger men he had met since becoming homeless. At first, the three lived in a maze of rusting iron beams left over from Big Dig construction.

One September day, sitting in a chair at a table built from an old cable spool, Mr. Gurney couldn't say enough about the kindness of the construction workers. Holding up a container of low-fat cottage cheese, pointing to boxes of doughnuts, and then at a full-sized futon - all gifts from Big Dig workers - he told a Globe reporter: "They're very nice."

In the fall, Big Dig officials forced the homeless men to move. The three settled one block south, where construction workers helped them build the 6-foot high shack they've been living in ever since.

The space was cramped, but the men made the best of it. They decorated their hut with stuffed animals and other trinkets. Barely visible one recent night beneath a half-dozen heavy blankets, and asking a reporter to buy him some booze, Mr. Gurney said: "It isn't so bad. It could be much warmer, though."

A few days later, emergency workers found him dead, wrapped beneath the same unwashed blankets. A preliminary report by the state medical examiner's office said Mr. Gurney, who had asthma and suffered from heart and liver ailments, may have died from natural causes - causes surely not helped by sleeping for a month in unrelenting cold.

Though she hadn't seen him in decades, Denise Perkins said she will always remember her uncle as a "barrel of fun," someone who, when she was a kid, would whirl her around her kitchen. "He was really good to us."

Mr. Gurney's body will be released from the medical examiner's office tomorrow and taken to the Veterans National Cemetery in Bourne. Sometime this week he'll be buried there, according to officials from the New England Shelter for Homeless Veterans, who are providing an honor guard to send him off with a full military ceremony.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe