By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2003

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2003Three months ago, Vannessa Turner was in charge of a small unit, drove a 5-ton truck through ambushes, and wherever she went in Iraq, the Army sergeant held her M-16 at the ready.

The single mom's war ended in May, when she collapsed in 130-degree heat, fell into a coma, and nearly died of heart failure.

Now, after more than a month recovering in Germany and Washington, D.C., the muscular Roxbury native spends her days riding city buses to ward off boredom, roaming area malls looking at things she can't afford, and brooding over how she and her 15-year-old daughter are suddenly homeless, sleeping on friends' couches and considering moving into a shelter.

"I almost lost my life in Iraq - and I can't get a place to live?" said Turner, 41, who Army officials say is the first known homeless veteran of the war in Iraq. "Yeah, I'm a little angry. Right now, not having a home for my daughter is the greatest burden in my life."

Though Army officials said they're trying to help, Turner, still wearing a leg brace and limping from nerve damage in her right leg, blames the service for not doing more.

When she went to the Veterans Administration Medical Center in West Roxbury after coming home last month,

officials there told her she had to wait until mid-October to see a doctor. When she asked the Army to ship her possessions from her unit's base in Germany, where she lived with her daughter for more than a year, they told her she had to fly back at her own expense to get them herself. And when she sought help to secure a veterans' loan for a house in Boston, she said mortgage brokers told her her only real option was to move to Springfield or Worcester.

officials there told her she had to wait until mid-October to see a doctor. When she asked the Army to ship her possessions from her unit's base in Germany, where she lived with her daughter for more than a year, they told her she had to fly back at her own expense to get them herself. And when she sought help to secure a veterans' loan for a house in Boston, she said mortgage brokers told her her only real option was to move to Springfield or Worcester.The Army acknowledges "mistakes were made."

"The Army can be a bureaucracy, but there are people in the bureaucracy who want to help," said Major Steve Stover, an Army spokesman. "I don't think it's acceptable for anyone to be homeless, and I believe most people in the Army want everyone to take care of each other."

Unfortunately, Turner is unlikely to be the last soldier serving in Iraq to return without a home.

Although veterans make up just 9 percent of the US population, they account for about 23 percent of the nation's homeless, according to the Washington-based National Coalition of Homeless Veterans. In a given year, of the 2.5 million people who become homeless in the United States, about 550,000 are vets, many of whom served in Vietnam and suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

But many are also like Turner - physically disabled, unemployed, and unable to afford their own place.

"In a country as wealthy as ours, with the best military in the world, it's outrageous veterans become homeless," said Linda Boone, the coalition's executive director.

Raised by her mother and grandmother in Roxbury, Turner earned a scholarship to study at Saint Mary's College in Moraga, Calif., where she graduated in 1984. She moved to Los Angeles to become an actress. When it proved difficult to find a job, she returned to Boston and soon gave birth to her daughter, Brittany. Over the next decade, she held a variety of low-paying jobs, working as a ticket agent for airline and bus companies, as a security officer for local universities, and as a performer in a few dance groups.

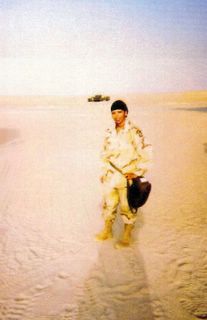

Then one day she saw an Army commercial and thought life in the military might really be, as the ad promised, a way to be all she could be - a way beyond the dead-end jobs, a way to learn new skills, earn decent money, and see the world. She enlisted in 1997 and served in Saudi Arabia, Korea, and Germany, before the Army sent her to Kuwait in February.

A cook and driver who thrived on the discipline of military life, Turner remained close to the front lines after her unit crossed into Iraq in April. "The hardest part was the unknown," she said. Guerillas ambushed her convoy while she traveled to Camp Balad, 40 miles north of Baghdad. "There were snipers all around us, and I kept thinking: `God, don't make my daughter motherless'."

Not long after dawn on May 18, Turner stood in a long line, waiting to buy food. Perhaps it was the heat, the 70 pounds of equipment she wore, or an ointment she used to protect herself from all the sand fleas, she said, but she started to feel dizzy. The last thing she remembers, she couldn't breathe. She collapsed, medics forced a breathing tube in her mouth, and she was taken away in a helicopter.

A few days later, she awoke in Germany with her mother next to her. The military flew her to Washington, where she stayed under close observation until doctors at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center released her July 10.

Discharged from the Army, a friend drove her back to Boston. Since then, she and her daughter have gone from the couch in her mother's cramped one-bedroom apartment, to a friend's couch, to her sister's friend's friend's couch, she said. She has little money - she sent much of her combat pay to help her brother and sister, who's also homeless - and feels uncomfortable about imposing on relatives and friends, most of whom have little space to provide.

So now, she and her daughter's clothes and possessions are scattered around town and the two aren't sure what to do.

"It's aggravating - I like having my own stuff and I don't like invading other people's space," said Brittany, who this week slept in a cramped Roxbury apartment, on an air mattress with two cousins. "It shouldn't be this way."

Not sure whether her case is a fluke, Turner wonders whether other veterans should expect the same treatment. In the past two weeks, the Army has promised to ship her possessions back from Germany, she's seen doctors at the veterans' hospital, and she's been told to expect her first disability check next month.

But the help, she said, only came after the office of Senator Edward M. Kennedy intervened. For example, she said, the Army refused to fly her brother and sister to Germany to bring her daughter home. Then the senator's office called and suddenly a flight was offered.

"Was that a coincidence?" Turner said. "I don't think so."

Veterans' officials, both nationally and locally, now know about her case and vow to make it a priority. "I don't know how she fell through the cracks. She really shouldn't have," said Tom Kelley, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Veterans Services. "No veteran, especially a wartime veteran, should be homeless."

Wearing a bandanna around her head to cover bald patches caused by trauma from her collapse, and refusing to cut off her hospital wristband, Turner hopes things improve before her daughter starts school next month. As angry as she is about the military's treatment, she hasn't given up on the possibility of reenlisting when her medical condition is reviewed next year.

"I think I like being a soldier better than being a veteran," she said.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe