By David Abel | Globe Staff | 07/18/2002

Bob Heard knows how to inspire dread in men, but something isn't clicking with this one man, the only one not wearing a tie.

All around, suited strangers chitchat cheerfully, as if professionals at a business meeting. What stands out about this one man isn't his breach of the dress code, it's his scowl.

"Why are you here?" Bob demands. "You know, if you act like a jerk, and I perceive you as a jerk, I'm going to treat you like a jerk."

The men and women before Bob this spring morning are homeless addicts, nearly all with long criminal records - in short, society's most down and out. Amid rising homelessness, state budget cuts, and Congress forcing more welfare recipients to work, it's this 6-foot-6, 300-pound former fugitive's job over the next three weeks to prepare this most unprepared group to find work.

If he fails, it means those assembled here may be stuck in the purgatory of shelters or, worse, again craving needles and sleeping strung out on the streets.

When Bob addresses this crew in a classroom at the Pine Street Inn,

he sees long-haired men in pin-striped suits and women with long nails and teased hair. There's a teenage dropout. A middle-aged hustler who traded sex for drugs. An alcoholic who dreams of being ambassador to Pakistan, and another just hoping to sweep floors.

he sees long-haired men in pin-striped suits and women with long nails and teased hair. There's a teenage dropout. A middle-aged hustler who traded sex for drugs. An alcoholic who dreams of being ambassador to Pakistan, and another just hoping to sweep floors.Among them is Ron Hayden, a brawny, bald-headed former engineer who was president of his high school class, married his high school sweetheart after college, and earned enough working for his father's firm that he once built his own home.

There's Stephenie Jackson, a single mother of five with graying dreadlocks who stood out so much growing up in Roxbury that she won a scholarship to Milton Academy, where the Kennedys sent their children.

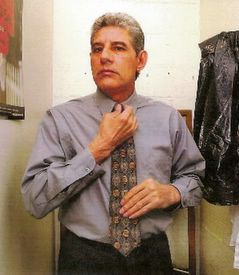

And sitting quietly, dressed like an executive with slicked gray hair, charcoal suit, and oval glasses, is Jesus Rodriguez, who believed he was embarking on a better life when he came to Boston after growing up without shoes, fishing for food, and living in a thatched-roof home in Puerto Rico.

Bob's outburst makes the three volunteers wonder whether they really want to be at this boot camp. As he approaches the security guard turned addict, the burly director - who for a decade served as security chief of the Black Panther Party - repeats his question, this time raising his voice: "Why are you here?"

The man blurts out: "Because I had to come."

Bob draws two faces on a board - one with a smile, the other a frown.

"Right now, all I see is a get-away-from-me, I-don't-want-to be-around-you attitude, and you're not gonna succeed that way," Bob tells him.

If he refuses to care how people perceive him, he'll miss the most important lesson. Success - a weekly check, healthy relationships, independence - requires what Bob calls "an attitude adjustment."

"The attitude you bring is the attitude you receive," he says, telling the still-scowling man, "It's not that I dislike you or anything, but you're a person who needs to be changed."

The man doesn't listen.

When he arrives the next day, again without a tie, Bob kicks him out.

Success masked a festering diseaseAs Ron watches the man smirk and sink into his seat, he sees himself: the resentment, the rebelliousness, the indifference. At 35 and in his second run through the program, Ron now recognizes how much he suffered from such an attitude.

The large, goateed ex-con seemed to have it all when he was young. In his senior year of high school in Sandwich, he ranked No. 7 in his class, played three varsity sports, and earned a spot to study engineering at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute. In college, he became the president of his fraternity. And after he graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering, married his longtime girlfriend, pocketed some money, and built a three-story Colonial in Mansfield, he seemed on track to take over his father's engineering firm.

But success masked a festering disease. The son of an alcoholic whose family had moved 12 times by his 13th birthday, Ron started drinking at age 10 - and began logging a history of arrests, drug abuse, and suicide attempts. "Alcohol and drugs were calling all the shots," he says.

After college, drinking nearly every day, he started blacking out. Eventually, his wife left, his father fired him, and he lost the house. It was 1995, he was homeless, and consumed with only one goal - finding his next fix.

His recent years are a blur of heroin, violence, jail, sleeping on the streets, recovery, and relapse. Things got so bad, Ron was pawning Christmas presents, holding drug dealers at gunpoint, breaking into homes, and getting arrested for everything from drunken driving to assaulting a police officer.

Ron has tried to quit drinking and drugging so many times now, going from detox to rehab to halfway house to work to jail, and back again, he's lost count. Now, after his last relapse in March, he lives at Pine Street's Anchor Inn, a strict substance-abuse program on Long Island.

Introducing himself to the group, Ron says, "It's hard to say my name without saying I'm an addict."

For Stephenie, recognition of her rage is new. The 39-year-old only recently stopped blaming others for her problems.

Two years after enrolling at Milton Academy, she quit. She missed Roxbury and didn't like being in a culture where teachers treated her like she was dumb.

By age 12, she started drinking, and because of abuse, she says, ran away from home. Later, she graduated from Boston Tech High School, but not before having her first child. And although she later earned an associate's degree in accounting, she never could distance herself from drugs. "You think you know it all," she says. "I was too smart for my own good."

The past 15 years, her life has paralleled Ron's: a haze of cocaine, alcohol, jail, and homelessness. The state eventually took custody of her children, she slept with men for drugs, and she racked up multiple arrests for dealing cocaine, welfare fraud, and other nonviolent crimes.

Until six months ago, however, she never acknowledged her addiction. "I didn't realize I was an alcoholic," she says, "until I was sitting in a police station being questioned, and the only thing I cared about was finishing my drink."

With a son serving in Afghanistan in the National Guard, a daughter finishing her master's degree in Virginia, and three young children still not in her custody, she's ready for change, she says. Introducing herself to the others, she says, "I'm here for some inspiration."

More bewildered than resistant, Jesus, a 53-year-old father of four, just has a hard time understanding his problems.

The oldest of 12 children,

Jesus quit school in the eighth grade to cut sugar cane, a job that paid only $7 a week. When his father saved enough money to send him to the States 35 years ago, his ticket to a better life seemed assured.

Jesus quit school in the eighth grade to cut sugar cane, a job that paid only $7 a week. When his father saved enough money to send him to the States 35 years ago, his ticket to a better life seemed assured.At first, things went well: He found a job at a rubber-parts factory paying $1.80 an hour. He married and had kids. But he felt out of place. He turned to alcohol, which went quickly from a few beers over the weekend to drinking whenever he had free time.

Then he met "Mrs. Heroin." The drugs took a toll: He was fired from jobs, his wife left, and he became homeless, sleeping in parks and spending time in jail for drunken driving, drug possession, and for failing to pay child support.

He has lived that way for decades now. "I know all the streets of Boston from walking them looking for heroin," he says. "That was my full-time job."

He's unsure he'll make it. "I'm clean now for a while, but I don't know what to do with myself," he tells the group in halting English. "I'm very confused. I'm just trying to find a way out."

'People need to know how to act'

The way out for Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus has always been clear: quitting drugs and alcohol. It also means paying debts, salvaging lost relationships, and finding a place to live. But there's one solution that's the key to all the others: getting a decent job - and keeping it.

That's the point of STRIVE. Founded two decades ago in Harlem, STRIVE tears into its students and tries to get them to question themselves: How did I get here? How do people see me? Who do I want to be?

The goal is to prepare people for work by instilling a few simple values - courtesy, honesty, optimism.

"All we expect are the things appropriate to succeed in the workplace," Bob tells the group the first day. "When you walk through the door and enter the workplace, you are walking on a stage. People need to know how to act."

When he left prison a decade ago, serving 13 years after being convicted of manslaughter for shooting a man dead, Bob was fortunate. He had a job waiting for him. It was a menial job at the Pine Street Inn, doing custodial tasks. But it was a springboard. In a few years, Bob became an administrator of one of the shelter's residential treatment programs.

With homelessness rising, the Pine Street Inn asked Bob to start a STRIVE program - the first one in the country tailored for the homeless. Everyone would get a supply of business clothing, helping them comply with the program's dress code. There would be no coddling. If people didn't follow the rules - showing up on time, following instructions, and opening up to criticism - they'd be dismissed. Just like at a job.

On average, a third of each class is booted, and even those who graduate often don't make it. Three-and-a-half years later, only about a quarter of the nearly 400 graduates have reported employment.

With the program costing the shelter about $200,000, there's pressure to improve the results.

"We work to get better numbers, but I don't expect much better," Bob says. "This is a very difficult population to work with."

Standing before Ron, Stephenie, Jesus, and the others every morning, the program's trainer, Nathan Saint-Eloi, forces them to examine themselves: How would you describe yourself? What are your weak points? What are your goals?

"In your suits, you look good on the outside, but now you need people to see you that way on the inside," says Nathan, 29, a STRIVE graduate who struggled with his own mean streak. "This is about shaping perception."

Then at the front of the classroom he hangs a sheet of paper with a picture on it, which looks to everyone like a portrait of an old man. But when he passes it around, it's a surrealistic image of a man, woman, and dog. "What we see," he says, "is what we think we see."

Later, Nathan asks everyone to describe their neighbor. It's an exercise in understanding how others see them, and a test of the thickness of their skin.

For Stephenie, that proves difficult. When Bob describes her as closed and arrogant, she stiffens. Flushed, she starts to vent: "I didn't want nobody to give me attitudinal training. All I wanted out of this was to sharpen my interview skills and get some help with my resume."

Then, suddenly, she bites her tongue. Her posture eases. "He set me up," she says. "I let him push my buttons, and I learned that you can't do that."

Preparation for the`ultimate blind date'

Some aren't used to smiling, or, for that matter, showering.

There are those for whom the term "eye contact" is unfamiliar jargon, a handshake requires practice - not too aggressive, not too weak - and the concepts of honesty and salesmanship need some explaining.

All these teachings come together in a job interview. To prepare them, Bob, Nathan, and the program's job director, Holly Johnson, badger them with questions, ranging from specifics such as, "Is it yours or the company's fault if the bus is late?" to the more open-ended, "Why should we hire you?"

Holly lays down the rules: Don't bring kids. Be aware of sweat. Never, ever, lie. And when it comes to criminal records, acknowledge any convictions but don't volunteer details.

"You have to look at a job interview as the ultimate blind date," she tells them.

For Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus, it takes some practicing. To "Tell me about yourself," Ron responds, "I am a hard-working, responsible individual who works well in a team."

Stephenie answers "What are your strong points?" by saying: "I'm honest, punctual, and I'm very reliable and dependable." For her weak points, she says: "Sometimes, I talk too much."

Jesus's difficulty is the language barrier. To the question "Why should we hire you?" he says: "I am easy to learn. I get along with people real good. I am very responsible. I like to be on time. And I don't need to be supervised."

After practicing their answers, writing resumes and cover letters, and studying the right body language, they are ready for the test: a mock interview before Bob, Nathan, and Holly.

No one volunteers to go first.

Then, Stephenie, in a white suit, brown pumps, and her dreadlocks tied back, steps up.

She walks up to the three and in one fluid motion smiles, shakes their hands, and explains she has come for a food-service position. Bob says he misplaced her resume. She slides a copy across his desk.

This is what they want to know: Why have you been out of work for so long? What areas do you need improvement on? How well do you react to criticism?

To the last one, she says, "I'm very open, and I see criticism as an opportunity to learn."

They can't stump her. She even smiles. Bob is impressed. When he asks if she has any questions, she wonders when they plan to hire, if there's a chance for upward mobility, and whether they have a tuition-reimbursement program.

"What do you want, everything?" he says, smiling.

When Jesus goes, he's hesitant. As he approaches his interviewers, looking stylish in a navy tie and gray suit, his eyes are heavy and he says, "I'm not sure I'm ready."

He shakes hands without making eye contact and leans back in his chair, looking drowsy.

"You're here for what position?" Bob asks.

"Uh, driver," he says.

He starts fidgeting and sweating. When Nathan asks how he works under pressure, Jesus responds: "Pretty good, um. Pressure is something that you, uh, when you looking at where it comes from, you deal with it . . . I shouldn't say that."

"What areas would you identify as weaknesses?"

"I don't really know how to answer the question. People tell me that communicating is a problem, but I try to communicate as best as I can."

When it's over, he knows it. Jesus becomes first to fail. He has to repeat the interview - and pass - to graduate.

"My mind went blank," he says, after passing his second interview. "I couldn't say anything."

For Ron, it's a breeze. If Stephenie showed poise, Ron oozes enthusiasm. He bounds into the interview with a smile, an assertive shake, and he tells the three he has come for the cook position.

He also sells himself. Why would someone with an engineering degree want to be a cook? "I recently rediscovered a passion for cooking," he says. "I enjoy being creative."

But when Nathan asks about his worst mistake, he reveals a little too much, discussing the "painful learning experiences" of abusing drugs and committing crimes. Though he passes, Bob and Holly say they would have reservations hiring him.

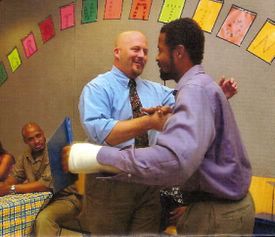

A sense of success on graduation dayWith jazz in the background, a spread of pork ribs and chocolate cake, 12 of the 17 people who began the program three weeks ago are graduating.

For some, the ceremony before family, friends,

and case workers ends with a question - Now what? For others, it means heading to another training program. For Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus, it means using what they learned to land a job.

and case workers ends with a question - Now what? For others, it means heading to another training program. For Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus, it means using what they learned to land a job.O

ver the past three weeks, they've maintained a routine similar to a normal workday. They rose early, caught a bus or the T to the Pine Street Inn, and then prepared to do it all again at night, ironing clothes and finishing homework.

Though ordinary habits for most people, they're a daily accomplishment for everyone in the group, and for some, graduating represents the first time they've ever completed anything.

"Your lives are all full of pain, but now you know something new - you know how to succeed," Bob tells them.

Nathan adds: "This is your life. It's up to you."

Her grandmother beaming by her side,

Stephenie thinks how she wanted to quit. Now, with a real job interview in the works, she's glad she stuck it out. "This is the best thing that's ever happened to her," says her grandmother, Evelyn Jackson.

Stephenie thinks how she wanted to quit. Now, with a real job interview in the works, she's glad she stuck it out. "This is the best thing that's ever happened to her," says her grandmother, Evelyn Jackson.For Ron, just three months removed from his latest relapse, it's a much-needed confidence boost. "What I needed was to go somewhere every day and feel good about myself," he says.

As for Jesus, who has quit or been fired from just about everything he has ever started, graduation is a completely foreign experience.

"For so long I've done nothing; this is really a big deal for me," he says. "I don't know how to explain it real good. But for me, it means that I did something I never did before. I never finished nothing. I always went back to the drugs. Just to finish something. I feel good about that."

'Can you start next week? '

Ron is used to highs and lows, but this jolt hits hard. When he arrives at the shelter after graduation, there's a note for him to call home. Ron knows what it means. His grandmother has died.

A few days later, back from the funeral, where he saw relatives whose lives all turned out far better than his, he's in a pit of despair. "Here I am: alone, broke, and I have to go find a job," he says later.

Then he gets a message from Holly. The dozen resumes he's sent out have met with little response, but she has a promising lead at a trendy Back Bay restaurant called Barcode. They want to interview him the next afternoon for a job as a cook.

At 5:30 a.m., he wakes with the 40 other men bunking in his room at the shelter. He takes the last bus from Long Island, across the harbor bridge, and knocks around the city, watching people in the Public Gardens. He kills time reading cookbooks and looking up recipes. Before heading to Barcode, he stops at a nearby coffee shop, wipes his bare pate and puts on a tie. He's wearing two undershirts to stop the sweat.

And then, despite all the nerves and preparation, it's over. The head cook just has one question: Can he start next week?

"There were many times I wanted to be dead, and now I finally have something to feel passionate about," he says. "It's like God closes one door and opens another."

Jesus doesn't have as much luck, but not for lack of trying.

A lot of the time, now, he spends at the Boston Public Library, practicing addition and subtraction, reading English, and scribbling in workbooks for a class preparing him to earn a high school equivalency diploma.

Two weeks after completing STRIVE, he has his first interview at an organization called On the Job, which employs cleaning crews. Despite forgetting his interviewer's name, he impresses her with his poise, confidence, and, of course, his impeccable appearance. Unfortunately, she tells him, there are no jobs left. So she sends him to Macy's and Filenes. But when he gets there, they tell him they have no jobs available.

"I will keep trying," he says.

Stephenie has a friend she's pretty sure is setting her up with a job at a local Souper Salad, but it falls through.

In addition to job hunting, she's taking computer classes and attending relapse-prevention meetings at the Dorchester treatment center where she lives. Then, through another friend, she finds out about a job at Marche, a buffet-style restaurant in the Prudential Center.

A few days later, in a pantsuit and sunglasses, she arrives an hour early to scope the place out. She drinks coffee to calm down, but she's still nervous. A few college students, who don't appear to have showered for the occasion, are waiting beside Stephenie. As a restaurant official calls them into another room, one of the students says, "It's not a big deal if I don't get this job - I've already got two jobs."

When Stephenie comes out after a 10-minute interview, she has a big smile. "It went very well," she says. A few minutes later, the friend who told her about the job and works at Marche ambles over with an even bigger smile. Would she like to take a tour? the woman asks. And, oh, by the way, she says, "You got the job!"

Looking at the gourmet desserts and tall sandwiches, Stephenie nods and says: "This is going to be very good."

'A normal life, that's all'

Nearly two months after graduation, Ron and Stephenie are the only ones of the 12 with a job. The rest are in the same boat as Jesus, in training programs, looking for work, or both.

By now, Ron has a healthy, if sleepless, routine.

Five days a week, the muscle-bound cook dons a white coat

and checkered bandana and mans the kitchen at Barcode. On his first day, he burned a few croutons, but now he has memorized how to make meals such as roast sirloin with mushroom gravy.

and checkered bandana and mans the kitchen at Barcode. On his first day, he burned a few croutons, but now he has memorized how to make meals such as roast sirloin with mushroom gravy.Returning to the shelter around midnight and having to rise and dress around sunrise, he's feeling the toll. But he insists he can handle the stress and isn't worried about working at a bar - the kind of place that has caused him so much suffering. As for now, he's saving money and hoping it leads to independence.

"A normal life, that's all," he says.

With a red scarf around her neck and a large beret wrapped around her dreadlocks, Stephenie spends her days making sandwiches and salads, and, on occasion, smiling for customers.

The work is hard, but it's a good job. She has friends there, too, including one man she grew up drinking and smoking with. If anyone's future looked dismal, she thought, it was his. Now, he's a supervisor at Marche, and he recently bought his own home.

Stephenie is thousands of dollars in debt, but if she can follow in her friend's footsteps, she'll be satisfied. "I can do this," she says.

Jesus has been clean now for the longest time since first getting hooked on drugs in his 20s - and now, for the first time in years, he has direction.

But also heavily in debt, his time running out at the shelter, and a need to mend relations with his family, he's eager to start providing for himself. He recently returned to an organization called Community Work Services, which months ago tried to help him find a job.

"I don't want to be a pessimist anymore," he says. "I am trying to do something."

It takes time to smooth out the street

When Bob looks back at the three, he has no illusions - and for good reason.

The next relapse, he knows, is just one sip or hit away. No matter how far they get - new jobs, apartments, relationships - Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus will always be addicts, always struggling to stay clean, always fearing that at any time for any reason they could lose it all again.

"You're always waiting for it to happen again - for the bottom to fall out any time," Ron says.

Little more than a month after starting his new job, it does. Overwhelmed by the stress of working late and rising early, he misses the bus back to the shelter and decides, on a whim, to stop at a bar. Before he knows it, he's swilled more Cape Codders than he can recall - and it's pointless to go back to Anchor Inn. This late, they'd require a urine test and he would be kicked out.

Now, back on the streets, barred from the shelter where he spent much of the past year, and still working at Barcode, he says: "I'm trying to avoid this turning into a catastrophic setback."

Bob sees an understanding in Ron for the need to change. But he knows that's not enough. "The real test is in the action - what happens now," he says.

In Stephenie, who has kept up with her job and recovery, he sees a lingering edge: "She still has roughness she needs to smooth out," he says, "but it takes a while to smooth out the street."

And, of all, Bob's perhaps the most impressed with Jesus. Though still searching for a job, he's finally taking control of his life. "It's not just his hunger to change," he says. "It's that he really did."

For addicts such as Ron, Stephenie, and Jesus, who have repeatedly sought but failed to lead normal lives, change can be fleeting. Given their seemingly endless cycle of relapse and recovery, is it futile to keep trying?

No way, Bob insists.

"Is that what we want to do as a society - give up?" he says. "As long as they're breathing, I don't think we should ever stop trying. We'll keep them alive until they decide to change. But they have to make that decision; we can't do it for them."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe