By David Abel | Globe Staff | 6/19/2003

For weeks, he watched them guzzle liquor in the park across the street. He saw one man defecate in the open of a nearby parking lot. And by the time he stumbled across the couple humping in a sleeping bag on the sidewalk beside his home, Fran Flaherty had enough.

When the lifelong Southie resident recently asked the lovers to leave, he said, they attacked him, gouging out his eyes, mauling him with a brick, and leaving him with nine stitches and a collection of painful bruises.

"In all my life, I've never seen it as bad as it now," said Flaherty, a 47-year-old father who lives in the same Bolton Street home where he grew up. "It's crazy - it's like they're everywhere."

Since spring arrived, he and other neighbors say they count more people panhandling, rifling through the trash, and otherwise appearing up to no good. To stem a rise in the numbers of people living on the streets, an annual rite with warmer weather, local leaders have arrived at a controversial solution: banning outreach efforts.

The reason the homeless stay in South Boston, they argue, is the large white van from the Pine Street Inn. For more than a decade, roving from Broadway to parks like the one across from Flaherty's home to encampments in abandoned fields, it has delivered blankets, soups and sandwiches, and free medical care to anyone in need.

A few weeks ago, shortly after the couple attacked Flaherty, Jim Kelly, the neighborhood's veteran city councilman, met with police and the city's homeless advocates to deliver this message: the van should not return to Southie.

"I told them whoever is coming here to give aid and comfort to the derelicts are doing a great disservice to our neighborhood," Kelly said. "It's just an encouragement for them to settle in ... We should not be encouraging people to break the law, especially when they're living in our parks and harassing our neighbors."

Controversy is not new to the Pine Street Inn's outreach

efforts. Since the shelter began sending teams of social workers and nurses out in 1986, neighborhoods around the city have raised questions about the van, recently including residents of a condo complex near the Boston Public Library, who voiced similar complaints about outreach efforts and eventually barred the van from visiting a group sleeping on steam vents there.

efforts. Since the shelter began sending teams of social workers and nurses out in 1986, neighborhoods around the city have raised questions about the van, recently including residents of a condo complex near the Boston Public Library, who voiced similar complaints about outreach efforts and eventually barred the van from visiting a group sleeping on steam vents there.Outreach workers and officials at the Pine Street Inn understand concerns about their work. But they argue the problems will only get worse if they can't reach out to those most in need.

"We're not a take-out restaurant service," said Shepley Metcalf, spokeswoman of the Pine Street Inn. "We do bring clothing, blankets, and food. But the real mission of the van is to establish relationships with the most vulnerable groups, and to encourage them to come off the streets."

And nearly every night, they do that. In addition to relieving the suffering of someone sleeping without a blanket or someone who may not have eaten that day, the outreach workers often do their best to coax some of the most recalcitrant street people to come in for the night or just to meet with social workers. Moreover, a doctor who travels with the van twice a week, often provides them medical care and persuades many to visit him at a free health clinic in the city.

City officials in Boston's Emergency Shelter Commission, who are trying to resolve the standoff, declined to comment.

But outreach workers are concerned about a long delay in contact with Southie's scores of homeless. "The problem is not going to be solved by ignoring it," Metcalf said. "There has to be a broad-minded strategy, and hopefully, some compassion."

Asked if there was any room for compromise, Kelly, who brandished recent police reports of homeless people arrested for everything from exposing themselves to assaulting one another, said: "I suggested they could come back, so long as they take the derelicts with them."

If the strong stance comforts Fran Flaherty, a construction worker who's a cousin of the city's at-large councilman Michael Flaherty, it's bad news for the men and women who live on the neighborhood's streets.

Already, police and city officials have dismantled shanties built in the park next to Flaherty's home and torn down an elaborate structure that housed at least a half-dozen people in an abandoned field beside the new convention center.

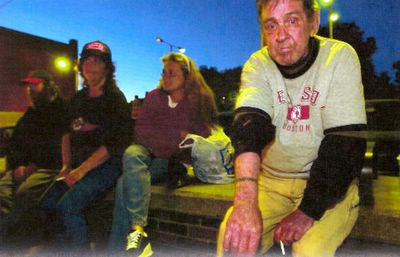

Perched one recent night atop a wall along Broadway, a gaggle of homeless people who called themselves the "Wall Nuts" bitterly complained about not seeing the outreach van in weeks.

"Just because one person got into a fight, they take out on the rest of us?" grumbled Liz Grenier, 46, who like the others said she has lived in Southie her whole life.

Homeless for several years since her boyfriend died, she said, she now sleeps inside the vestibules of ATM machines. "We're starving to death and it would nice to have a blanket at night," she added.

Next to her, Phillip Fisher explained why the group didn't leave for another part of the city, one where the van still visits every night.

"This is our town, and we're not going to be kicked out," said the 58-year-old who has lived on the streets for the past three decades. "They'll have to throw us in jail to make us leave."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe