By David Abel | Globe Staff | 9/16/2002

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 9/16/2002

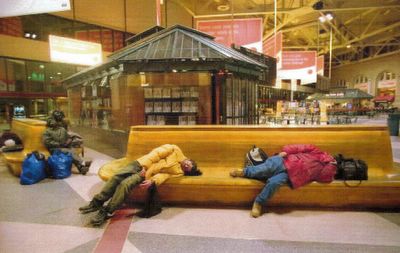

The rows of vinyl seats where she used to sleep are all gone. New checkpoints have blocked off a few preferred nooks and the mood has changed, with stocky officers in black fatigues and combat boots holding large, menacing rifles.

There's something else different about Logan Airport - a lingering eeriness, a missing excitement, and most egregious of all for her, a disappeared community.

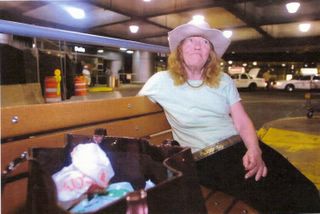

Before the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, Judie Jones and at least a half-dozen elderly women spent nearly every night blending in with travelers and sleeping in secret spots throughout the terminals. A year later, with the size of the security staff doubled and the airport enforcing an old rule barring the homeless, few if any of the women have returned.

The changes have upset Jones, a short, Shakespeare-quoting 67-year-old who calls Logan her home. But the chain-smoking native of Australia doesn't blame airport officials or the once-dreaded troopers, who she now says are "beautiful to watch." The blame, she says, squarely lies with "that swine, bin Laden," whom she calls a "hurricane of hysteria" and a "pusillanimous excrescence."

"On Sept. 11 last year, you broke my heart and the heart of every decent, law-abiding American," she wrote to him in an "open letter" from "the lady who loves Logan."

In another missive to the wanted Al Qaeda leader, she added, "It's not so much what you've done to a group of homeless people. We'll survive. But how dare you change the fun, the bustle, and the excitement that was Logan!"

For years, especially during the winter, the state troopers at Logan often looked the other way when running into Jones and the other women they had come to know. Others, who presented problems, were often put in cabs and sent to shelters, as the airport's policy instructed. But since the attacks, the airport has maintained something close to a zero-tolerance policy.

"It's a whole new ballgame here," said Phil Orlandella, a Logan spokesman. "I don't think anyone looks the other way anymore. We get calls now for anyone who looks or acts suspiciously - and sometimes those people are homeless. We have to be careful."

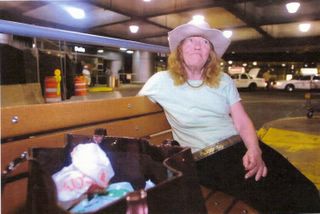

On a recent night at Logan, Jones, wearing a large felt Stetson,  a pair of well-worn flip-flops, and a gold necklace over a lime blouse, lugged two handbags, searched ashtrays for cigarette butts, and, as has long been her custom, hunted for abandoned Smarte Cartes, returning each for a quarter. "It's good fun, like the poker machines in Vegas," she said.

a pair of well-worn flip-flops, and a gold necklace over a lime blouse, lugged two handbags, searched ashtrays for cigarette butts, and, as has long been her custom, hunted for abandoned Smarte Cartes, returning each for a quarter. "It's good fun, like the poker machines in Vegas," she said.

Picking up a half-filled cup of ice coffee someone left for trash, and between puffs of a whole cigarette from a friend, she winked and said, "I can see why I might be vaguely suspicious."

The outspoken woman with bright blue eyes, auburn hair, and creased cheeks that frame a nearly toothless smile says she has returned to the airport because people there treat her like "an international traveler, a human being who they call ma'am.' " It's also a way of earning as much as $15 a day returning carts.

"If I had my choice, I would live here again," she said.

To visit for the day is one thing. To return to sleep, though, is too risky - she's afraid she might get arrested.

On Sept. 11, 2001, when she learned about the hijackings while at a job conference, it began to dawn on her that she too would be directly affected. Her home would be locked down with security forces, she worried, ready to shoot at anyone who didn't seem to belong.

"Under no circumstances would I go to the airport - it was too scary," she said. "Who knows what would have happened?"

That night, and through the spring, Jones, who speaks French and German and once studied Latin, stayed at the city's homeless shelter on Long Island. After feeling confined, complaining about her living conditions, and running into problems with the shelter's staff, she moved to the Erich Lindemann Mental Health Center on Staniford Street in Boston when a social worker found her a bed there.

Fed up again with her living situation, the prickly woman pines for the serenity she felt in the well-cleaned lounges at Logan, where she could always find leftover meals, an interesting conversation, and classical music to sooth her as she fell asleep.

Terminal A, where she used to sleep on occasion,  was recently razed to make way for a more modern facility. The cops are more likely to growl than they are to flash a smile. And her old acquaintances are nowhere to be found: Marie, a gray-haired woman who always wore a suit and said she was waiting to catch a plane to meet her grandson in New York; Elizabeth, who wore a turban and had food to share; and Peewee, an eccentric who often offered her cigarettes.

was recently razed to make way for a more modern facility. The cops are more likely to growl than they are to flash a smile. And her old acquaintances are nowhere to be found: Marie, a gray-haired woman who always wore a suit and said she was waiting to catch a plane to meet her grandson in New York; Elizabeth, who wore a turban and had food to share; and Peewee, an eccentric who often offered her cigarettes.

On her first trip back to Logan in December, she wondered, "Where were the people? Where was the laughter? Where was the holiday happiness? . . . They've turned my home into a ghost town."

As time has passed, she feels more secure, as if life at Logan is returning to normal, or at least a new normal. There's the constant crawl of taxis. The great mix of people from all over the world. The food and financial opportunities. And, during the day, when there are even a few other homeless people, the old feeling comes back. "Who's to say I'm not a Parisian world traveler?" she said.

But, eyeing one of the muscular troopers toting a large assault rifle, she added: "I wouldn't dare come back to sleep."

With $6 in quarters in her purse and sipping from the cup of ice coffee, Jones smiled, watched the steady flow of pedestrians stream into the airport, and said, "My sense of optimism has returned. Logan is like America - the phoenix rising from the ashes."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Previous story:

AT LOGAN AIRPORT, A LOUNGE LIFE

HOMELESS WOMEN KEEP BAGS PACKED AT TERMINAL

By David Abel

Globe Staff

7/21/2001

For Judie Jones, home is a place that spans 2,400 acres and moves 80,000 people a day.

The petite 66-year-old from Australia is one of at least a half-dozen elderly women who spend nearly every night somewhere in the terminals of Logan International Airport.

"The skycaps, porters, and security people all come here to work, but, darling, this is my home," Jones says. "It's like Bob Hope used to say, but for me it's true: Airport waiting rooms are my real home."

Like the other "Logan ladies," as she calls them, Jones - a former substitute teacher and aspiring novelist - does her best to blend in. She dresses nicely, lugs around a Smarte Carte stacked with neatly arranged bags, and showers as often as possible.

"If someone asks what I'm doing, I say, `Oh, I'm just in from the Cape' or `I'm in from LA,' or, if I'm in the right mood, I say, `I'm just in from Paris.' "

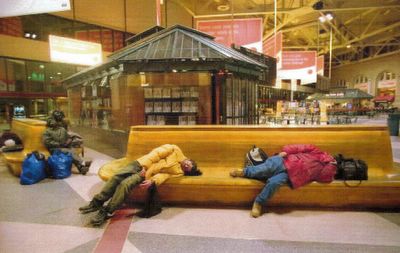

Still, once the gates to most airlines have shut, the food courts have closed, and midnight passes, it's not hard to tell that the short woman stretched out comfortably across the vinyl seats of Terminal A intends to spend the night.

Officially the Massachusetts Port Authority doesn't allow anyone to live at the airport, which is open 24 hours a day. About a decade ago, when the homeless began descending on Logan in large numbers, Massport started sending them to shelters in agency-subsidized cabs. "This is a public facility; it's not a place for people to sleep," says Phil Orlandella, a Logan spokesman. "That is our policy and that will be our policy."

The state troopers who enforce the policy, however, use their discretion. They kick out the vast majority who hang around the airport, especially young men. But in spite of a memo this month warning that the homeless are "harassing employees and travelers," troopers let the older women stay.

"We call them our resident homeless," says Albert Manzi, who for years has worked the graveyard shift at Logan. "We do our best to get them to a better place, but some of them just like it here. They don't cause us any problems."

One trooper who asked not to be named said he won't evict certain people in the winter. Once, on a night when the temperature dropped below zero, a Massport official told him to remove one of the women. "I couldn't do that," he recalls. "I just took her to a different terminal."

Even among the slew of bonafide travelers sprawled out throughout the airport, Jones sticks out. She frequently quotes Shakespeare and compares herself to "a pushy broad like Ethel Merman." She cheerfully boasts about finding her colorful pants suit at the "Salvation Army Boutique." Her frizzy strawberry blond hair and craggy, sunburned skin frame a nearly toothless smile.

Manic, she rifles through crumpled dollar bills and cigarette butts stuffed in her plastic purse, sorts piles of papers in an old shopping bag, and scatters bags of junk food.

The commotion could easily give her away - and that would be a bad thing, she says. Like many homeless people, Jones loathes shelters, complaining they're overcrowded and dangerous. "There was so much brutality at the shelters that I couldn't stay there anymore," she says, calling Boston's Night Center "The Fright Center." "I thought, `Where else could I go that I would be shown humanity and treated with the graciousness of an international traveler?' "

At Logan, she feels safe, comfortable, and free to come and go as she pleases. She has also had good luck here. The troopers have only ordered her to leave once, she says. And Jones gets along well with them, enough so that she merrily introduces a reporter to troopers at the airport substation.

Arriving in the States shortly after divorcing her husband in 1988, she says, she has moved around, living everywhere from Las Vegas to San Antonio to Columbus, Ohio. Her last stop before Boston was Providence, where a string of bad luck first forced her onto the streets and where she discovered the perks of sleeping at an airport, she says.

A year ago, Jones caught a bus to Boston. She stayed in shelters for a few months until realizing she would be far more anonymous in the ever-churning world of Logan than at Providence's smaller T.F. Green Airport.

There are also distinct benefits to living at Logan. The airport is carpeted and clean, the bathrooms well maintained, there's air-conditioning, and the place abounds with leftover meals, sodas, and dropped change.

There are TVs to watch, what Jones calls "the best available selections of smokable cigarette butts in the whole of Boston," and there are often "presents" available, including airline personal care kits. "What a difference between the quality of the items handed out by Air France and the quality handed out at the shelters!" she says. "The deodorant is a brand-name spray, compared with that awful stick I've had to use."

There are even moneymaking opportunities. When she is low on cash, Jones walks around the airport, collecting scores of abandoned Smarte Cartes and returning each for a quarter. "I feel much more at home here because I can be a person of the world, not some statistic," she says, snatching another clump of butts from an ashtray outside Terminal E. "It's big and it's free and there's no oppression. It's really a fascinating place. The views are great, for which I pay nothing. I love watching the airplanes and the sunrise. And another thing: There's always someone to talk to."

Well after midnight, she runs into some of the other ladies. Marie, a gentle gray-haired woman in a rumpled blue suit with a pretty blouse, and a Filene's shopping bag on her wrist, could be anyone's grandmother.

"How's everything with you, Judie?" Marie says in a soft brogue, politely declining a stranger's offer to bring her some food and insisting she's about to catch a bus back to the city. When Jones leaves, she whispers, "The poor love. She doesn't know what day it is, she's been here so long."

Around the airport, Jones points to a few others who live at Logan but blend in with the late-night travelers. "That man is deaf," she points to an older man asleep in Terminal C. She opens the door to a bathroom in Terminal E, and a large 74-year-old woman named Mary is snoring on a bench next to a Smarte Carte.

Pointing to her resume, clumped with an old shopping bag filled with letters and articles she has written for Boston's homeless newspaper, Jones declares that she would make a perfect candidate for a job in Logan's public relations office. "How many people know this airport better than I do?" she says, adding that she has a master's degree. "How many are as attached to it as I am?"

After applying recently, Massport sent her a curt letter: "They basically said, `Thanks, but no thanks,' " she says.

Near bedtime around 3 a.m., on her way to her secret nook at the airport, a place she calls "No Man's Land," the old lady finds a spare pillow and blanket on a bench someone must have left from a recent flight. "Wonderful," she says. "Isn't life fun?"

Lying on a clean metal bench hidden away by two large display cases of model airplanes and a broad window looking over the great sprawl of Logan airport, Jones squints into the fluorescent lights and slips on a pair of old sunglasses. "Do I look glamorous or exhausted?" she jokes.

Then she shuts her eyes and tries to sleep, before the morning traffic wakes her.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/24/2004

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/24/2004

Something happened when he raised his voice.

The quiet, chubby student, so polite around campus he answered professors "yes, sir" or "no, ma'am," seemed to channel the guttural roar of a southern preacher. As he thundered about the need for justice or the plagues of poverty, it was like his colleagues at Boston College Law School were witnessing the second coming of Martin Luther King Jr., a young man whose zeal, many believed, might one day propel him to the highest offices of the land.

Then he made the two-hour commute to his home for the past year, a musty room where he slept on a thin, vinyl mattress among hundreds of men crowded into one of the city's largest homeless shelters. There, isolated at the island refuge in Boston Harbor, the aspiring attorney often seemed like just another junkie, walking about aimlessly and hurting so much for the next high he sometimes begged others for money.

Arthur Cornelius Harris, a 27-year-old who made it from the ghetto to a few months shy of graduating one of the nation's top law schools, managed to bridge two very different worlds, and two very different identities.

But as he lurched toward a bright future, charming judges, professors, and friends while disguising a secret none imagined, he couldn't escape the darkness of the past, a place where, he once wrote gratefully: "The early grave that calls for me is still empty."

BORN INTO A LAND of preachers and agitators, his relatives among the vanguard who marched for civil rights, Arthur's upbringing in Montgomery, Ala., rarely emerged from the shadow of his city's history. "As black men in America today," his grandfather would tell him, "you have a debt you can never repay."

Given all the poverty, despair, and drug-driven violence around him, which he saw as the legacy of slavery, Arthur felt what he called an "awesome responsibility" to "make America live up to her promise of equality and justice."

The first challenge was surviving.

A latch-key middle child who grew up in one of Montgomery's most dangerous housing projects, Arthur's mother admonished him and his older brother to never open the door or answer the phone, unless it rang five times, until she returned home from her job as a hotel housekeeper.

But the then-scrawny boy couldn't escape the violence, no matter how adroit he became at talking his way out of trouble. Over the years, a neighbor, who enticed the fatherless boy with gifts, such as shoes and shirts, sexually abused him. And later, when his mother thought he was running with the wrong kids, she beat him up so badly, police held him for several days at a shelter for child abuse victims, eventually returning Arthur to live with his grandfather for several years. "I would whup them with a belt, wherever - wherever," said Mona Scott, his mother. "I wanted them to be afraid of me, to protect them."

When Arthur went to elementary school, one of only two blacks in his class, he would come home and say, "My name is not Arthur; my name is 'nigger.' That's what the kids call me."

Despite all the hard times, the boy with the oddly long arms began to stand out. In the fifth grade, he already showed a flair for speaking before a group, precociously articulate for a boy. "Whatever I required, he would go beyond the call of duty," said Rosa Abernathy, who taught Arthur in elementary school and later saw him whenever he returned home. "He was one of the best students I had in more than 40 years of teaching."

By the time he reached high school, after years of listening closely to the call and response at Sunday-morning services in the Baptist church near his home, he found his voice. Then having won election as president of his sophomore class and treasurer of the local youth group of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, he found his calling -- to be an "activist," as he would later proudly call himself.

Arthur earned respect through persistence. While holding a job as a cashier at a local drugstore, he kept score at basketball games, organized dances, performed in plays, wrote for the school newspaper, and once, one of the gangs at his junior high school tried to recruit him to help them with their schoolwork. As teachers watched him walk so purposefully around town, often passing an African head shop sign that read "Welcome to the Ghetto," they would say: "Look at that Arthur Harris. He's off to something."

Keeping busy helped him bottle up the inner turmoil -- the anger of meeting his father only once, when he was 15, the separation for most of his high school years from his mother, the repeated stops by police whose profile he often fit, and the struggling with his sexuality while relatives and reverends told him he would go directly to hell if he didn't mend his ways.

"I challenge anyone to go to my middle school or high school, live in my neighborhood, and come out any better than I did," Arthur wrote later. "Most yield to the grave, the prison, the drugs, or some other escape route. I was lucky."

FOLLOWING HIS MOTHER'S advice to leave Montgomery, and aiming to become the family's first college graduate, Arthur was admitted to the University of Alabama at Birmingham, 90 miles north of home.

Walking around campus in a conservative suit, with one pin or another fastened on his lapel, and often flashing his big smile, Arthur quickly made a name for himself among the campus's 10,000 undergraduates.

"I've never had a student touch me like Arthur," said Niyi Coker, a professor of African-American studies who became a mentor to the young man. "There was something special about him -- you just knew he was going places."

Though he found the schoolwork challenging and had to work fulltime as a stock boy at the campus bookstore and as a cashier at a local drugstore, Arthur made time for extracurricular activities.

Like Martin Luther King, he majored in sociology and  joined the prestigious black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, where he served as chaplain and led brothers on volunteer missions to local soup kitchens. Soon, Arthur sought a larger stage, and he practiced for it. As a freshman, standing sideways in front of his dorm-room mirror, he would put one hand in his pocket, extend the index finger of the other one, and rehearse theatrically stabbing the air.

joined the prestigious black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, where he served as chaplain and led brothers on volunteer missions to local soup kitchens. Soon, Arthur sought a larger stage, and he practiced for it. As a freshman, standing sideways in front of his dorm-room mirror, he would put one hand in his pocket, extend the index finger of the other one, and rehearse theatrically stabbing the air.

By his senior year, he had served as president of the student government, chairman of the Black Student Union, president of the Omicron Delta Kappa National Leadership Honor society, and membership on everything from the university's mock trial team to the local YMCA's mentor program.

The titles were not mere resume builders. Arthur took his positions seriously -- and the administration took notice.

Once, he happened to pass the university president having her hair done in a local beauty parlor. Cornered, he unleashed a litany of student gripes. Then he told her how he thought she should wear her hair.

"He was the king of boldness," said Bettina Byrd-Giles, the assistant director of student programs while Arthur served as president. "He would say things no one else would dare."

He also learned how to attract the attention of those beyond campus.

To protest budget cuts in the university system, he led hundreds of students from schools around Alabama to the state capitol, eventually persuading lawmakers to rescind many cuts. When university trustees proposed severing the medical school from the campus, he organized a movement that hounded the trustees until they abandoned the idea. And when administrators suspended black fraternities and sororities for missing a campus meeting, he held a rally that attracted hundreds of students and local media, ultimately winning a lift of the suspension.

"Arthur was the type of student who made the administration scared," said Jalon Alexander, a friend who Arthur pushed into student politics and who eventually succeeded him as president. "By the way he spoke, he could make you believe in anything he wanted."

If administrators feared Arthur, they also respected him.

When President W. Ann Reynolds ran into him behind the counter of a drugstore, and realized how little money he had and how he sent much of it home, she decided - without telling him - to pay his tuition his senior year, $3,200. Then, after hearing Arthur was accepted to a special pre-law program for promising minorities at Suffolk University Law School, she used her frequent flier mileage to cover the cost of the flight to Boston.

"It was the best money I ever spent," said Reynolds, noting Arthur probably had more of an effect on the university than many administrators. "I wish I could have done more."

SINCE HIS TEENS, Arthur believed a law degree provided the key to power, the key to righting all the wrongs he saw around him.

But when he applied to some 20 law schools, none admitted him, the result, most likely, of never becoming a proficient test taker. So when he learned about the Council on Legal Education Opportunity's summer program in Boston, an intense 7-week course which offered him the a chance making it to law school, he decided to come north.

In 2000, standing on Boston's Freedom Trail for the first time, he wrote, "I was reborn right there on the spot by a thought … that somehow I had survived … I had finally made it out."

A few weeks later, he did something almost no other student has done before: Arthur talked his way into Boston Law School.

On a visit to Suffolk, Elizabeth Rosselot, BC Law's assistant dean of admissions, found herself in a room with Arthur, listening to him speak with "a fire" she had never seen in a prospective student. "It's usually about 'I, me, and mine,'" she said. "What I saw was just an incredible determination to beat the odds."

A half hour later, she promised him a spot in the class of 2004.

When he arrived a year later, after struggling to finish his math requirements in Alabama, the initial euphoria wore off quickly.

The first year of law school proved grueling, and Boston, the north, was different than he expected -- colder, not just in its climate, but less welcoming than he imagined.

Uneasily out of the closet and living among mostly well-off white students, Arthur thought he made a mistake, that perhaps he should drop out and move to Canada, or somewhere else he might escape homophobia and racism. As time passed, he would become indignant about law school and the "suburban" professors, who he saw as teaching more about process than action, about how to abide by the system instead of how to improve it.

"I too have a dream," he wrote in a paper titled "A Burning Desire for Justice" in the fall of his second year. "I am not like Thurgood Marshall, who only wanted a good legal job after law school, but ended up fighting for civil rights because there were no other opportunities … I came to the law with an understanding that I was to use it as a tool, to help stop the modern-day tidy ethnic cleansing of my people."

Fond of quoting the late Senator Paul Wellstone, he often urged people to "never separate the life you live from the words you speak." To many, he did just that.

Once, after discovering a website that charged the Coca Cola Co. with assorted barbaric acts, he refused to drink Coke, making his friends go from restaurant to restaurant in search of a place that served Pepsi. When a military recruiter came to campus, Arthur signed up for an interview and let the officer know how he felt about the military's policies excluding gays. And last year, while attending a local anti-war protest, Arthur whipped out his own bullhorn when he found the rally not quite spirited enough.

"Only Arthur could chastise people at an anti-war protest for being apathetic," said Sam Lieberman, a close friend of Arthur's at the law school.

Then he decided to move into a homeless shelter.

THE WAY HE EXPLAINED it, the abrupt decision seemed to make sense. After all, his friends and professors thought, this is Arthur Harris, not the typical law student.

When he moved in little more than a year ago, he told them he wanted to live with the people he planned to represent after school, because "sometimes," he explained, "you have to get down in the hole with them, in order to pull them out."

But not everyone bought Arthur's explanation, and though he assured them he would be fine and there was a method to his perceived madness, he confided to a few that there was another reason for his moving into the shelter - money.

Arthur had been living a ways from the law school, in an undergraduate dorm, working as a resident assistant. Although the job, which he didn't like, provided free room and board, the federal loans he received required the compensation - a value of about $8,000 - be deducted from his financial-aid package.

"He definitely preferred getting the money," said Christopher Strader, a fellow resident assistant and another of Arthur's close friends on campus. "He didn't like living alone. He was lonely."

He also seemed depressed, frequently confiding in friends and professors that he felt out of place, that his creativity had been drying up, that he wanted to drop out of law school, where he was diagnosed with a nonverbal disability and earned mostly Cs. Around the same time, reeling from a bout of unrequited love, he told friends he thought about buying a wedding ring, to avoid questions about his sexuality.

A year later, long after judges, professors, and friends welcomed him to live with them, many wonder whether Arthur had another reason for living in the shelter, one he refused to reveal.

"It seemed, at first, like a completely irrational decision to live in a shelter if you didn't have to," said Mary Ann Chirba-Martin, a professor who described him as "a fish out of water" at law school. "Perhaps he found a piece of home there."

TO GET TO THE SHELTER, Arthur usually took public transportation from the Newton campus to the Boston Medical Center, where he waited for a bus that took him and scores of other homeless men and women more than 10 miles away, through Quincy, down a desolate road and across a rickety bridge to one of the old quarantine hospitals on Long Island.

When he first arrived in December of 2002, the shelter assigned him a social worker and a bed, No. 313. "He said he had no family, no friends, and no support, and he didn't know what he would do," said Valerie Pruitt, who served as his case manager and knew Arthur attended law school.

The two kept in touch over the months, mostly by phone or e-mail. When Pruitt offered Arthur the possibility of moving into a better shelter - a recovery program where he might have his own room - he said he wasn't interested.

Over the year, Arthur made several good friends at the shelter, most of whom couldn't understand why he chose to live in a place they would have left in a hot minute. He found a lover there, but then something happened. In September, at 31, Ricky Negron, suddenly died, one of eight homeless people to die last year as the the result of a heroin overdose.

The loss devastated Arthur.

"He would say, 'I wish I was with Ricky - I wish he didn't have to die,'" said Robert Wooden, 52, a friend from the shelter.

A few months before, other friends noticed, Arthur had started acting strangely. "He would come up to me and ask me for $10 or $20," said Leon Smith, 21, who spent weekends going to the movies or eating out with Arthur.

Then Smith and others noticed a pattern: Arthur would return from school around 7 p.m., eat dinner in the shelter's cafeteria, and then walk the refuge's dark corridors, hunting for what he called "pop."

It was a good night, when he found it and had the money.

"He liked the way it made him feel, and he encouraged me to try it," Smith said. "It got rid of the depression and made him joyous. He would come up and kiss me and sing, 'There's no me without you … I'm so happy to be alive."

As summer gave way to fall and the cold of Thanksgiving blew over the island, Arthur began seeking a more direct high. Rather than sniffing the white powder, he asked David Johnson, a 35-year-old veteran junkie who slept a few beds away, to teach him how to shoot up the heroin.

"He didn't really understand the road it was taking him down," Johnson said. "I wanted him to look at my life, to see how awful it is, and how it's like we're all in a boat, pulling different oars, sinking."

ON THE EVENING OF Nov. 22, after e-mailing friends about his plans to return to Alabama to promote his latest cause - electing Howard Dean president - he hopped off the bus and sat down for dinner with his friend Carlos Ramirez.

As they devoured a plate of rice and beans in the shelter's cafeteria, Ramirez noticed something wasn't quite right about Arthur.

"Who's got pop around here?" he kept asking Ramirez, 23, who met Arthur a few months before at another shelter in Boston.

Later, after dinner broke up, Ramirez found Arthur on the shelter's third floor, in the TV room. He was wearing shorts and sandals, but sweating profusely.

"He was a wreck," said Ramirez, who noticed his eyebrows looked puffy, his eyes red, and a white powder coating his upper lip and nostrils. "He looked like he was going to blow up."

Ramirez touched his arm, but Arthur didn't seem to feel anything. "I said, Arthur, what's wrong with you?"

Shortly after, he saw Arthur hunched over, his eyes rolling and dilating. As Arthur slowly made his way to the bathroom, he assured Ramirez he was fine. "Don't worry about me," he said.

At 5:30 the next morning, when Arthur hadn't cleared out with the 143 other men on his floor, shelter officials found him in bed.

He was dead.

HOW COULD A YOUNG man who had so much promise and who regularly preached against such poison have fallen into the trap of the most dangerous, addictive drugs?

"Arthur loved everyone," said Niyi Coker,  his professor at the University of Alabama. "He fought everyone's causes, but in the final analysis, Arthur forgot to love himself, and in doing that, he cheated the world of everything he could have contributed."

his professor at the University of Alabama. "He fought everyone's causes, but in the final analysis, Arthur forgot to love himself, and in doing that, he cheated the world of everything he could have contributed."

When his mother learned of Arthur's drug use, she couldn't believe it. "He lived a double life," Mona Scott said. "I guess he knew not to tell me, because I would've been up there in a minute, escorting him to classes, if necessary."

At Boston College, where he managed to keep his drug problem a secret, administrators, professors, and friends couldn't understand the contradiction -- of how much Arthur, in the end, actually separated the words he spoke from the life he lived.

"It makes me think he must have been in pain, a lot of pain," said Norah Wilie, the law school's assistant dean of students, who added Arthur's name would be noted during graduation this year among the students listed in the class of 2004. "It's hard to understand why people can make such tragically bad choices."

And for many of his closest friends, who knew him only as a wellspring of inspiration and a model for anyone to pattern their lives, the loss of Arthur represents the defeat of a force for so much good.

"I thought Arthur was going to change the world - I felt that deep in my bones," Christopher Strader said. "That's what's so sad. The world's going to be completely normal without him."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 12/03/2002

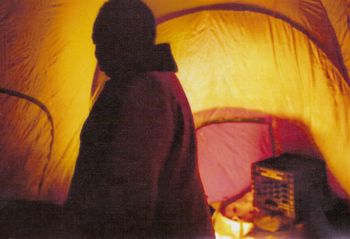

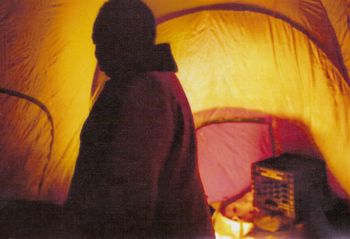

From his secret perch in the woods, the hermit watches the morning light spread over the pond and seep through a patch of trees, sprinkling a golden haze over his humble home. At night, when the raccoons leave their lair in the beech tree and the birds nest until morning, he wraps himself in a heap of blankets and takes comfort in the stillness.

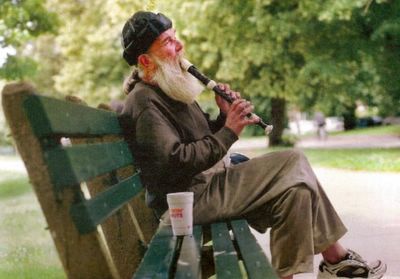

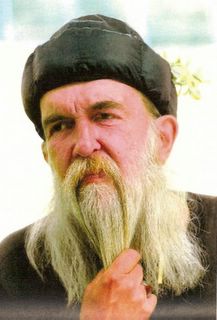

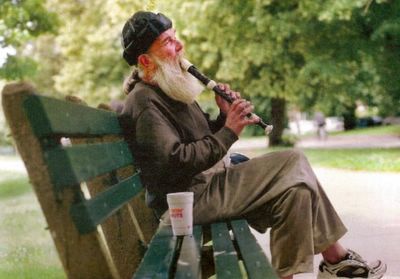

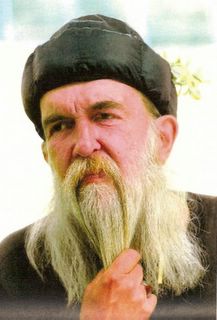

A self-proclaimed philosopher, Donald Keaney revels in escaping the quiet desperation of the city. But unlike another solitude-savoring New Englander, who more famously sought answers to life's persistent questions beside another pond in the woods, the shaggy 61-year-old hasn't left, nor given up its many conveniences.

For the past 17 years, Keaney, the son of a French horn player for the Boston Symphony, has found a way to lead a rustic existence in the middle of Boston - living in a self-made tent in the woods near Jamaica Pond, less than a mile from the middle-class Brookline home where he grew up.

Like Henry David Thoreau, whom he has long admired, Keaney loathes government and can't be bothered with social conventions, such as paying rent or concealing his opinions. And though he has enough money, he has little desire for more than the barest of essentials - a plastic tarp for a roof, a half-dozen heavy blankets, and the 11 newspapers he reads every day and stacks around him by the thousands.

"Living outside with nature means living in the most intimate way," says Keaney, who was raised by a Jewish mother and Irish father and calls himself a "Lepre-Cohen." "It's peaceful, no one bothers me, and there's no better place to read than under natural light."

One of a hard-core group of homeless who refuse to sleep in city shelters, Keaney and about 300 wizened men and a few women live outdoors throughout the year, doing what they can to survive Boston's hottest days and coldest nights.

While he spends much of his time alone in the woods, Keaney makes his way downtown nearly every day, dining in soup kitchens, speaking out at rallies and lectures on college campuses, attending classical concerts, and collecting his newspapers. He also visits friends - a few homeless guys he buys food for and talks politics with. And occasionally he ventures to Watertown to see his sister, who hosts him for holidays such as Passover and receives his subscriptions to a half-dozen conservative magazines, including The National Review and Weekly Standard.

Esther Keaney, an Ivy-League educated accountant with her own business, isn't sure how her brother ended up on such a different path. He doesn't do drugs or drink, she says, and as a beneficiary of a trust fund left by a wealthy aunt who worked as a secretary for Fidelity founder Edward C. Johnson, he can certainly afford an apartment.

"I don't believe there's any mental illness, though it's possible," says his sister, who has urged him to find a more permanent place to live. "I just think he genuinely likes living in the woods."

Donald Keaney began sleeping outdoors when he was young and went to camp in Maine, where as a gifted clarinetist he won awards for his chamber music. Over the years, he sought more isolation, living for months at a time in New Hampshire's White Mountains and the Maine woods. Yet the freedom of living alone, on his own terms, hasn't always translated into an idyllic life.

Like anyone without a home, he has suffered his share of indignities. Thieves have stolen his sleeping bags, pillaged his tents, and walked off with his blankets. Sometimes, when he can't make it back to the woods, he spends the night in vestibules for ATM machines. And at least once, he says, someone tried to kill him while he was asleep.

"While we have a lot in common, Thoreau and I have led very different lives," he says. "I'm not a romantic."

His sister worries he's not taking care of himself. He doesn't shower much, his teeth are rotting, his nails are long and dirty, and his beard and hair are unruly. None of that bothers Keaney. He's more concerned about staying warm, which he does by wearing layers of heavy wool sweaters, staying out of sight, and keeping abreast of current events.

A self-described "paleo-conservative," who believes in less government, less immigration, and less politically correct public debate, he spends much of his day poring over his newspapers, including The Wall Street Journal, Investors Business Daily, the Globe, Herald, Harvard Crimson, Christian Science Monitor, and The New York Times, Post, and Daily News.

When he's done reading, he uses some of the papers to insulate his tent, little more than a tarp upheld by twine. The rest he keeps for future reference, neatly stacking them on small branches and in plastic bags. His collection of tens of thousands of newspapers - some of which are now covered in moss - dates back to 1991.

"I'm someone who speaks the truth," he says. "You have to know what's going on to speak the truth."

One truth he prefers not to publicly acknowledge is his precise location in the large stretch of woods. The last thing he wants, he says, is more visitors.

While Keaney's home is camouflaged by a thicket of oaks, pines, and hemlock trees, the property owner knows he's there. But without any complaints about his presence, and sure after all these years he's not doing any harm, they let him be.

"He likes to be alone and we don't want to interfere with him," says James Karloutsos, who maintains the property which Keaney asked not to have identified. "As long as he takes care of the environment and himself, we let him live his way."

Social workers who know Keaney say unlike many other visitors to soup kitchens, he helps wash dishes and mop the floor after meals.

"He's quiet, conscientious, and very much his own person," says Macy DeLong, executive director of Solutions at Work, a social services provider in Cambridge, which has given Keaney tickets to classical concerts.

On a recent morning in the woods, with freezing rain pelting his plastic tarp and a cutting wind rustling his newspapers, Keaney hunches over a recent copy of The Wall Street Journal. Wrapped in a heavy wool sweater and several military-grade blankets, his solitude interrupted, he talks about the "illusions" of liberals, the "brilliance" of the Constitution, and his "Manichaean" or good-vs.-evil view of nature.

"Living in the woods, you can see life is very tragic," he says, explaining how he watches hawks pounce on other birds and raccoons chase other raccoons. "It can be no different with people. I don't know if I'm a misanthrope, but we have a lot of limitations."

Offering an extra sweater and blanket to his visitors, he flashes the first, if slight, smile when asked if he's content with his choices. He leans closer, pauses, and says:

"We are what we are, and we are responsible for who we are."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 5/04/2003

The snoring starts as soon as the lights go out. When the bus leaves its corner, most conk out, knowing well after so many trips that this is likely to be two of only four hours of sleep tonight.

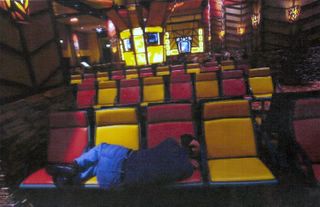

For some passengers on the late bus to Mohegan Sun, the rigid seats in tight rows aren't just beds for the night, they're the closest thing they have to a home.

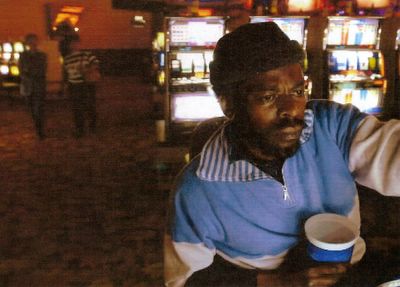

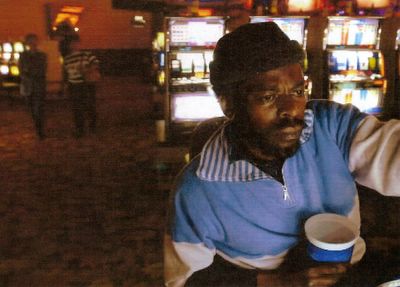

Some on the packed tour bus are sojourners for a night of gambling, others are high-rolling addicts who often make the all-night trip to the enormous casino in Uncasville, Conn. But for a few like Assaad Lahoot, who rides the bus nearly every night, there's a different attraction than the "legendary gaming experience" advertised.

Most of all, the lure is shelter. Other perks: the free food and drinks. There are also many diversions. Aside from playing slots or staring at the roulette wheel, there's the live entertainment, ways to make money (other than gambling), and, importantly, the lounge where they can sneak some sleep while pretending to watch TV.

"This is my life - it's much better than sleeping on the streets or in a shelter," says Lahoot, 51, one of scores of homeless people who descend on Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods nearly every night and do their best to blend in.

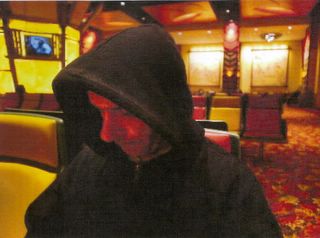

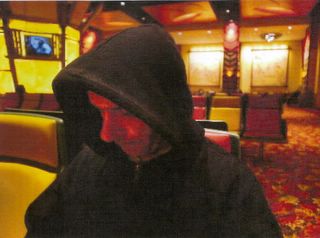

With his sweatshirt's hood pulled over his head and his body curled on the back three seats of the darkened bus, the former house painter, whose four children remain in his native Lebanon, explains how he survives:

Unable to find a painting job because of a bum arm, he says, he often spends his days standing on corners distributing a company's coupons. The little money he earns, though, is enough to afford the $10 bus ticket to the casino. After a day hanging around downtown avoiding trouble, Lahoot walks to Chinatown to catch the 9:30 p.m. bus.

In addition to the trip to the casino, the ticket comes with a $15 voucher for food or merchandise at the casino, and two $10 coupons he can use as chips for gambling. Like other drifters at the casino, if he finds a buyer, Lahoot may sell both, the voucher usually fetching $6 and the coupons $10.

The $6 profit - assuming he doesn't gamble it away - often leaves enough to tip the bus driver and ticket taker a dollar each. "It's not a bad deal," Lahoot says, adding that the benefits include an all-you-can-eat buffet.

When the bus pulls into the reservation just before midnight, it parks next to dozens of other buses from New York and New England. Some 40 crusty-eyed passengers file out. Besides Lahoot and a few other homeless men, there's a young cook hoping to win some quick cash, a mother of eight looking to "relax" after working long hours at a nursing home, a recent immigrant from Ireland on a night out with a fellow telephone operator, and a balding salesmen who says the all-night trips to the seven-year-old casino have helped send his daughter to private school.

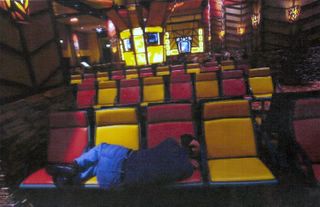

They enter the bus lounge, a brightly lit room where more than 100 vinyl red and yellow seats surround a large kiosk of several TVs. Sprawled on the seats are a mix of bedraggled visitors, some homeless, others exhausted from a day of gambling.

In the distance, through a marble hallway connecting to the 300,000 square feet of everything from blackjack to baccarat tables, are the indoor waterfalls, the 1,200-room hotel, and the plethora of high-priced shops and restaurants. Many of the regulars in the lounge, where there are only faint sounds of the incessant ringing from the thousands of slot machines, spend the whole night here - and the security guards know them well.

"They're not supposed to be sleeping," says John Barry , one of the casino's guards who struts around the carpeted floors talking into an earpiece. "We may nudge them a bit, but as long as they wear their shoes, we let them be."

, one of the casino's guards who struts around the carpeted floors talking into an earpiece. "We may nudge them a bit, but as long as they wear their shoes, we let them be."

There's John, a scruffy 40-year-old sometimes poker player who walks to the casino from Norwich, Conn., and says he's "traveling to Florida." There's Mary, an elderly Jamaican in a straw hat who spends nearly every night wandering around with a cane that she doesn't seem to use. And then there's Geri, a 58-year-old one-time resident of Las Vegas, who says she's done it all, from serving cocktails to singing as a showgirl.

Wearing large sunglasses studded with rhinestones and a black sequined dress, and with her lips painted pink, she sees a touch of glamour in her lifestyle. "Sometimes I'll spend several days here," says Geri, who like most visitors to the casino would only give her first name. "I like the ambience."

At around 3 a.m., nearly 24 hours after arriving on a bus from New York, Geri brushes on some more of the already heavy makeup, and describes her living situation this way: "You could say I'm in transition."

A few seats away, two regulars, both named George, nosh on large containers of pistachio nuts, paid for with the vouchers they received on the bus from Boston. One of them, a long-haired Asian man who says he makes his living by gambling, shows off a pricey pair of New Balance sneakers, which he bought with nearly a week's worth of vouchers. The 43-year-old dice player also shows off a pair of $200 sunglasses, which his friend bought in the same way.

Having long ago finished gambling for the night, the two Georges start arguing about whether casinos should be allowed in Massachusetts.

"People will satisfy their compulsions regardless," says the younger George, noting the thousands of jobs and millions in tax dollars a casino would bring. "Think of all the people like us. We wouldn't have to come here, and the money would stay in Massachusetts."

The other George, an 80-year-old Navy veteran and former radio operator who says he's been gambling nearly every day since serving in World War II, argues his friend's point is precisely the problem.

"I've been gambling 900 years and I know the odds are stacked against you," he tells his friend, whom he met riding the bus years ago. "It would be murder to have casinos too close to Boston. People like me would go every day - and we'd all be broke."

Not long before the bus leaves for Boston at 4:30 a.m.,  Lahoot ambles back into the bus lounge and slumps into one of the vinyl chairs. A man next to him has a jacket over his head. Another man stretches across three seats, unperturbed by the roving guards in turquoise jackets. Everywhere is the sound of snoring.

Lahoot ambles back into the bus lounge and slumps into one of the vinyl chairs. A man next to him has a jacket over his head. Another man stretches across three seats, unperturbed by the roving guards in turquoise jackets. Everywhere is the sound of snoring.

Lahoot boards the bus for Boston and mumbles something about losing money while playing roulette. He shrugs and settles into the same back seat.

He closes his eyes. Dawn is breaking. Another night has passed.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

His six-month ban from a city shelter was up the next day, but Jack McDonnell decided to die. Did it have to be that way?

His six-month ban from a city shelter was up the next day, but Jack McDonnell decided to die. Did it have to be that way?

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/07/2004

Before stripping off all his clothes, cursing the cancer that took his wife, and lying naked on the frozen ground, Jack McDonnell said he wanted to die.

He got his wish.

The call came in early last month, on one of the season's first frigid nights, for a man dancing naked in the streets near West Roxbury District Court in Jamaica Plain. When officers arrived shortly after dusk, they found the 58-year-old Vietnam veteran sprawled out beneath a bridge, in a cramped, fenced-off area strewn with garbage and teeming with rats. He was waiting to die.

One of hundreds of homeless men and women barred from city shelters on any day of the year - including the coldest winter nights - McDonnell was banned at the nearby Friends of the Shattuck Shelter, where he often stayed during a decade of homelessness. His six-month expulsion would have expired the next day.

When paramedics arrived around 6:30 p.m. on Dec. 4, the naked man remained conscious. They wrapped him in a wool blanket, fastened his cold body to a long board, and ferried him to the back of an ambulance, where the driver had the heat on full blast. Then he stopped breathing, and paramedics lost his pulse. A few hours later, at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, doctors pronounced him dead - the first homeless man authorities believe died of hypothermia this winter season.

Could McDonnell, a father of two and a former alcoholic-awareness counselor, have been saved? Did the city's safety net fail a man who became homeless after his wife died a decade ago? And how could a man who police and outreach workers knew was self-destructive, who nearly died of hypothermia once before and who was again drowning himself in alcohol, be left to sleep under the Arborway Causeway on a day when the temperature plunged to 22 degrees?

Some homeless advocates blame state budget cuts, noting the shelter recently laid off McDonnell's longtime social worker and that the Legislature last year slashed more than half of the state's detox beds. Others question why publicly subsidized shelters, the last refuge of the most downtrodden, are allowed to bar the homeless, sometimes for minor reasons. Some argue city police should have the power to take McDonnell, who had been well known to them for years, into protective custody.

"The system failed him, maybe even defeated him," said Joe Churchill, executive director of the Shattuck shelter. "You feel a sense of despair whenever you hear about a case like this."

Six-month ban

A well-known presence at the Shattuck since the early 1990s, McDonnell was barred in June after stumbling in drunk, cussing staff, and raising his fists when issued a warning, shelter officials said. Deemed a risk to the staff and other guests, administrators asked a state trooper to escort him off shelter property and inform him he wouldn't be allowed to return or obtain any of its social services for six months.

By the time of his death, McDonnell was among 103 people barred from the Shattuck last year for more than a day, 47 of whom had received similar six-month penalties. In 2002, the shelter banned 306 people - some indefinitely, some just for a day - for offenses including violence, stealing, selling drugs, sexual activity, bringing food into the sleeping quarters, and failing to follow staff directions or maintain proper hygiene.

Barring the homeless from shelters has long been controversial. Pushing people out of a refuge often defeats the efforts of outreach workers, who spend countless hours trying to persuade the hundreds of city residents who regularly sleep outside to come inside.

When the trooper booted McDonnell last summer - a fate that had befallen him before - the drunken homeless man vowed never to return, screaming "to hell with all of them," friends of his said.

So he moved under the bridge, where he befriended Tabetha Blanton, a 19-year-old who a year ago traded foster care for homelessness. The two often sang old songs together - tunes like "Build Me Up, Buttercup" - and she would help cut his hair, trim his beard, and mend some of the wounds he suffered from the random attacks street dwellers confront all too often. Once, someone slit his throat while he slept beneath the bridge, and later she used nail clippers to remove stitches from his neck.

Blanton encouraged him to return to the shelter, to appeal his case, as anyone barred can. But he refused. "He said he would never come back - he felt rejected," said Blanton, who called him "Grandpa."

More than a week after his death, she began to cry while remembering him. "I loved him," she said. "It broke my heart when he died." When she asked why he wouldn't stay in another shelter, she said he insisted: "I'm happy. I just need a blanket and a pillow."

Other friends said McDonnell thought it wasn't worth the effort of staying at another shelter. At the Shattuck, where he had become a part of the family, he had a bed reserved and kept many of his possessions in a locker. At other shelters, he told his friends, he didn't want to be packed in "like sardines."

In recent years, the state's homeless population has reached record numbers.

One night last month, a survey of 80 state shelters found they exceeded capacity by an average of 26 percent. The shelters, according to the Massachusetts Housing and Shelter Alliance, have exceeded capacity every month over the past five years.

"There aren't enough beds," said David Lewis, 53, a former carpenter who knew McDonnell for two years and joined him under the bridge after also being barred from the Shattuck. "He didn't want to go to the Pine Street Inn or anywhere else to sleep in a chair or on the hard floor of the lobby."

Safety concerns

As cruel as barring may seem during the winter, shelter officials say it's an unfortunate necessity.

Although they acknowledge barring has sometimes-deadly consequences - at least six people barred from city shelters, including McDonnell, have died in the streets in the past four years, outreach workers say - their first obligation, they argue, is the safety of the majority of guests who follow the rules.

"If we could save everyone, we would do that," said Deborah Farrell Nelson, a spokeswoman for the Shattuck.

But with more and more people cramming every night into already overcrowded shelters and fewer dollars and staff to oversee them, she and others said, the necessity for barring has only increased in recent years. At the Shattuck, which accommodates 110 people every night in bunk beds and dozens of others on thin mats, budget cuts in the past year and a half have required shelter administrators to lay off one-third of their staff, including Ali Rashid, who had served as McDonnell's social worker and helped find beds for him and others at area detox facilities.

The problem, however, isn't the lack of money as much as it is the way the shelter system works, homeless advocates say.

Even if shelters had more money, advocates note, they don't employ sufficient staff with the medical authorization to treat the mentally ill and hard-core drug addicts, many of whom end up in the city's emergency shelter system. Moreover, the city lacks programs to look after those who are barred, protective-custody laws that would allow officers to forcibly remove people from the streets, or an organized hierarchy of shelters, in which police might be able to transfer scofflaws to a more secure facility. Now, when someone is particularly unruly, violent, or breaks the law, he often ends up in what many on the streets call the "Gray Bar Hotel" - jail.

Another problem, advocates say, is the shortage of detox beds. Last year, at a time when most detox centers had a waiting list, the Legislature cut the number of state-subsidized beds from 997 to 420, with many of the losses in the Boston area. Men like McDonnell would check into detox once or twice a month, to sober up for a while. The result, advocates say: At least eight of the city's 42 homeless deaths as of late December were the result of overdoses, significantly more than in previous years.

The city's lack of a protective-custody law - which would enable police officers, like those in New York, Philadelphia, and other northern cities, to remove the homeless from the streets on the coldest nights - makes it more likely people will die on the streets of Boston, advocates say. In 2002, 12 people died on the streets here, while advocates reported only 10 died in New York City, which has a homeless population more than six times the size of Boston's. In 2003, at least 1,400 street people died throughout the country, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

"These are all tough and complicated issues," said Dr. James O'Connell, president of the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, who argues the city should open small shelters to accommodate those who are barred. "I hate barring, but sometimes, given the way the system works now, it's absolutely expedient."

As far as promoting protective custody, which many outreach workers argue would push many of the homeless underground and make them harder to look after, O'Connell said: "This is a lingering and torturing issue. When is it OK for us to take away someone's rights? I don't know the answer."

But he and others believe more should have been done to look after McDonnell, who a few years ago was found lying in the middle of a road during a snowstorm and last year was found suffering from hypothermia, shelter officials said. Studies show a homeless person with a previous bout of hypothermia is seven times more likely to die of exposure if left on the streets, O'Connell said.

Back then, when Paula McDonald, who now runs the Shattuck shelter, served as McDonnell's social worker, she obtained a court-ordered treatment plan and had him involuntarily committed to spend a month sobering up at Bridgewater State Hospital. This time, with fewer resources and the bar preventing him from returning to the shelter, McDonnell slipped through the cracks.

"If the position of his social worker had not been cut," McDonald said, "I think there's a possibility he wouldn't be dead."

A generous man

A former garbage man who grew up in Hyde Park, according to shelter staff and friends, McDonnell rarely talked about his past, except when the vodka or whiskey got to his head and he dwelled on the cancer that claimed his wife, Maria, and thrust him to the bottle and a life on the streets.

Often in good spirits, the man with straw-colored, scraggly hair always let his friends know he was approaching. They could hear his voice booming down the street: "If it was good enough for Peter, it was good enough for Paul," they could hear him sing. "If he didn't have any money, he didn't have it at all."

Friends considered McDonnell a generous man, though his possessions, which were still under the bridge late last month, included little more than old Fila sneakers, an deflated air mattress, a cooler, National Geographic magazines, a wood sign reading "Need Coffee Truck," and what he called his "little shrine" of toy ducks and rabbits.

"If he had a penny, he would give it to you," said Jim Morgan, 48, who met McDonnell six years ago. Morgan pointed to a pillow and blanket that McDonnell gave him when Morgan, too, found himself barred from the Shattuck and living under the bridge.

Friends and shelter officials said they believe McDonnell had two sons but that he hadn't seen them in years. The only relative they know he kept in contact with was his mother, Mary McDonnell, who would meet him by the Forest Hills MBTA station to bring him money. She last lived in Roslindale, shelter officials think, but her phone number no longer works, and they aren't certain she's still alive.

At the shelter, despite his occasional outbursts, the staff liked McDonnell. Once, the shelter director said, he brought a big rose bush to the Shattuck and planted it beside the building. "It bloomed beautifully for two years," the shelter director said. "He would do nice things like that."

But McDonnell also had a temper, especially when he drank, which he did increasingly in recent months. Once the alcohol took effect, despair followed, friends and shelter officials said, and he would talk about joining his wife. It became a kind of mantra, so his friends under the bridge didn't take him seriously earlier last month when he began taking off his brown corduroy jeans and red flannel shirt.

Finally, one of them, a man who his friends call Jimmy K, put a blanket atop McDonnell. But he threw it off and kept muttering about his wife. After the sun set, friends said Jimmy K ran to a phone and dialed 911.

By the time police and paramedics arrived beneath the bridge and slipped through the small opening in the fenced-off area, they found McDonnell's body dangerously cold.

"There was a lot that could have been done that wasn't," McDonald said. "But what really killed Jack was his alcoholism."

McDonnell may have gotten his wish, but he's yet to join his wife. No relative has come to claim his body, and, for now, the man who spent the past six months of his life outside will, in death, remain inside, at the city morgue.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 7/14/2003

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 7/14/2003

CAMBRIDGE -- It's an annual rite of summer: Hundreds of homeless people leave city shelters to sleep on the streets, and everywhere, under bridges, in wooded areas, throughout the parks, are the mangy blankets, the empty beer bottles, and the trash they leave behind.

Natalie Hefflefinger, for one, can't stand the mess.

The petite 65-year-old spends her days singing in Harvard Square and her nights sleeping in a nearby park. Almost every evening, she takes the day's earnings to CVS, buys a box of trash bags - the good kind that don't break - and fills them to keep the parks clean. Sometimes, when she has enough change, she ambles along Mount Auburn and other area streets, dropping quarters in meters running low.

"It's a way to give something back," she said. "People think of the homeless as always taking from society. This is how I can thank society for letting me sleep in the parks."

One of scores of people who make the square their home, Hefflefinger doesn't want her adopted neighborhood to go to rot. Though the city has posted signs warning the homeless against sleeping in parks after dark, officials let many stay - especially those who help maintain them.

"If people store debris, sleeping bags, or build houses, we don't let that happen," said Lisa Peterson, commissioner of the city's Department of Public Works, which maintains more than 100 public spaces throughout Cambridge. "But some people can really surprise you."

The daughter of a gardener who grew up in a middle-class family in Malden, Hefflefinger has lived on the streets for years. She won't say how long, but her decaying teeth, scarred hands, and old, tattered boots attest to years of life without a home.

"Self-reliance isn't easy, but people have been very nice," she said, remembering the man who gave her $300 for cleaning up.

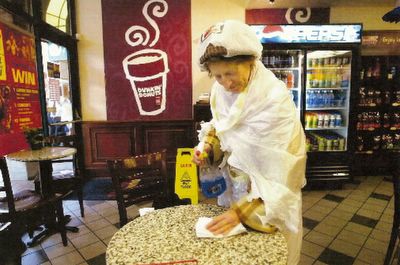

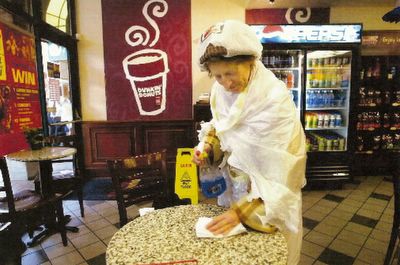

An artist who likes to draw landscapes - "I'm just an amateur," she said - and a singer with an interest in patriotic tunes - "I like to sing `America the Beautiful' " - the soft-spoken woman is one of the square's few homeless allowed to linger in local cafes.

She always pays for her coffee, and, after parking herself in a chair for a few hours, she pulls a bottle of Windex from her cart to wash off the table. She also tips.

"She's one of the most consistent tippers we have, always leaving behind a dollar," said Daniella Pinto, manager of the Dunkin' Donuts by the John F. Kennedy School of Government. "It's a pleasure to have her here."

Often, the cafes are the only shelter she has.  On a recent morning, after waking in Longfellow Park to a downpour, she used some extra garbage bags to craft a raincoat, tied a plastic 7-Eleven bag to her head for a hood, and covered her overstuffed shopping cart with a blue tarp. After walking around for a while, a mop, rake, and buckets hanging off her cart, she stopped in one of her regular haunts for coffee and a jelly doughnut.

On a recent morning, after waking in Longfellow Park to a downpour, she used some extra garbage bags to craft a raincoat, tied a plastic 7-Eleven bag to her head for a hood, and covered her overstuffed shopping cart with a blue tarp. After walking around for a while, a mop, rake, and buckets hanging off her cart, she stopped in one of her regular haunts for coffee and a jelly doughnut.

"Harvard Square is a good place for me. I like books and art," she said.

Pressed, she widens her blue eyes and admits she wouldn't mind a place to live. "I'm not doing so great, but I'm not falling apart," she said in a gentle voice. "The mosquitoes are wicked now."

Married twice with five grown children, she had a messy breakup and doesn't keep in touch with her family, whom she last saw years ago when they lived in Nashua. "I'd rather not get into it," she said. "I'm not looking for any charity."

A former secretary and onetime waitress, Hefflefinger wants to earn her keep. And though she accepts donations - many of her clothes are presents from strangers - she always tries to give something back.

What would she want the most if she could have it? A replacement for the prescription glasses she lost, she said. For now, though, the nights are warm, and that, in itself, is good. She refuses to return to a shelter, she said, preferring the freedom of the outdoors.

On another recent day, with her mop of brown hair twisting in the evening breeze, she had little time to talk. She worked - ensuring that not a scrap of trash or any of last autumn's crinkled leaves remained in Longfellow Park.

After a few hours of tidying up, with dirt caked in her fingernails and sweat filling her craggy cheeks, she stood proudly over 11 white trash bags, the park looking its summer's best.

Two at a time, she carried the bags to a nearby sidewalk, stacking them for the garbage truck to take the next morning.

"This is just something I can do," she said. "It's my way, I guess, of saying thanks."

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2003

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 8/21/2003

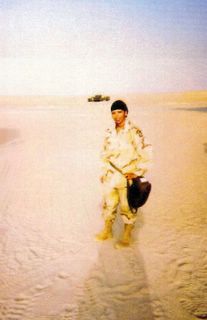

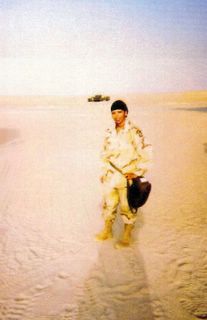

Three months ago, Vannessa Turner was in charge of a small unit, drove a 5-ton truck through ambushes, and wherever she went in Iraq, the Army sergeant held her M-16 at the ready.

The single mom's war ended in May, when she collapsed in 130-degree heat, fell into a coma, and nearly died of heart failure.

Now, after more than a month recovering in Germany and Washington, D.C., the muscular Roxbury native spends her days riding city buses to ward off boredom, roaming area malls looking at things she can't afford, and brooding over how she and her 15-year-old daughter are suddenly homeless, sleeping on friends' couches and considering moving into a shelter.

"I almost lost my life in Iraq - and I can't get a place to live?" said Turner, 41, who Army officials say is the first known homeless veteran of the war in Iraq. "Yeah, I'm a little angry. Right now, not having a home for my daughter is the greatest burden in my life."

Though Army officials said they're trying to help, Turner, still wearing a leg brace and limping from nerve damage in her right leg, blames the service for not doing more.

When she went to the Veterans Administration Medical Center in West Roxbury after coming home last month,  officials there told her she had to wait until mid-October to see a doctor. When she asked the Army to ship her possessions from her unit's base in Germany, where she lived with her daughter for more than a year, they told her she had to fly back at her own expense to get them herself. And when she sought help to secure a veterans' loan for a house in Boston, she said mortgage brokers told her her only real option was to move to Springfield or Worcester.

officials there told her she had to wait until mid-October to see a doctor. When she asked the Army to ship her possessions from her unit's base in Germany, where she lived with her daughter for more than a year, they told her she had to fly back at her own expense to get them herself. And when she sought help to secure a veterans' loan for a house in Boston, she said mortgage brokers told her her only real option was to move to Springfield or Worcester.

The Army acknowledges "mistakes were made."

"The Army can be a bureaucracy, but there are people in the bureaucracy who want to help," said Major Steve Stover, an Army spokesman. "I don't think it's acceptable for anyone to be homeless, and I believe most people in the Army want everyone to take care of each other."

Unfortunately, Turner is unlikely to be the last soldier serving in Iraq to return without a home.

Although veterans make up just 9 percent of the US population, they account for about 23 percent of the nation's homeless, according to the Washington-based National Coalition of Homeless Veterans. In a given year, of the 2.5 million people who become homeless in the United States, about 550,000 are vets, many of whom served in Vietnam and suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

But many are also like Turner - physically disabled, unemployed, and unable to afford their own place.

"In a country as wealthy as ours, with the best military in the world, it's outrageous veterans become homeless," said Linda Boone, the coalition's executive director.

Raised by her mother and grandmother in Roxbury, Turner earned a scholarship to study at Saint Mary's College in Moraga, Calif., where she graduated in 1984. She moved to Los Angeles to become an actress. When it proved difficult to find a job, she returned to Boston and soon gave birth to her daughter, Brittany. Over the next decade, she held a variety of low-paying jobs, working as a ticket agent for airline and bus companies, as a security officer for local universities, and as a performer in a few dance groups.

Then one day she saw an Army commercial and thought life in the military might really be, as the ad promised, a way to be all she could be - a way beyond the dead-end jobs, a way to learn new skills, earn decent money, and see the world. She enlisted in 1997 and served in Saudi Arabia, Korea, and Germany, before the Army sent her to Kuwait in February.

A cook and driver who thrived on the discipline of military life, Turner remained close to the front lines after her unit crossed into Iraq in April. "The hardest part was the unknown," she said. Guerillas ambushed her convoy while she traveled to Camp Balad, 40 miles north of Baghdad. "There were snipers all around us, and I kept thinking: `God, don't make my daughter motherless'."

Not long after dawn on May 18, Turner stood in a long line, waiting to buy food. Perhaps it was the heat, the 70 pounds of equipment she wore, or an ointment she used to protect herself from all the sand fleas, she said, but she started to feel dizzy. The last thing she remembers, she couldn't breathe. She collapsed, medics forced a breathing tube in her mouth, and she was taken away in a helicopter.

A few days later, she awoke in Germany with her mother next to her. The military flew her to Washington, where she stayed under close observation until doctors at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center released her July 10.

Discharged from the Army, a friend drove her back to Boston. Since then, she and her daughter have gone from the couch in her mother's cramped one-bedroom apartment, to a friend's couch, to her sister's friend's friend's couch, she said. She has little money - she sent much of her combat pay to help her brother and sister, who's also homeless - and feels uncomfortable about imposing on relatives and friends, most of whom have little space to provide.

So now, she and her daughter's clothes and possessions are scattered around town and the two aren't sure what to do.

"It's aggravating - I like having my own stuff and I don't like invading other people's space," said Brittany, who this week slept in a cramped Roxbury apartment, on an air mattress with two cousins. "It shouldn't be this way."

Not sure whether her case is a fluke, Turner wonders whether other veterans should expect the same treatment. In the past two weeks, the Army has promised to ship her possessions back from Germany, she's seen doctors at the veterans' hospital, and she's been told to expect her first disability check next month.

But the help, she said, only came after the office of Senator Edward M. Kennedy intervened. For example, she said, the Army refused to fly her brother and sister to Germany to bring her daughter home. Then the senator's office called and suddenly a flight was offered.

"Was that a coincidence?" Turner said. "I don't think so."

Veterans' officials, both nationally and locally, now know about her case and vow to make it a priority. "I don't know how she fell through the cracks. She really shouldn't have," said Tom Kelley, commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Veterans Services. "No veteran, especially a wartime veteran, should be homeless."

Wearing a bandanna around her head to cover bald patches caused by trauma from her collapse, and refusing to cut off her hospital wristband, Turner hopes things improve before her daughter starts school next month. As angry as she is about the military's treatment, she hasn't given up on the possibility of reenlisting when her medical condition is reviewed next year.

"I think I like being a soldier better than being a veteran," she said.

David Abel can be reached at dabel@globe.com. Follow him on Twitter @davabel.

Copyright, The Boston Globe

By David Abel | Globe Staff | 1/05/2003

It's when the shakes start, sometime after midnight or on a Sunday afternoon, that Michael McGlaulin sets out to score a bottle of "cheap whiskey" or what merchants call "wine for the homeless."

It's a stiff brew with a sharp aftertaste. But unlike other cocktails, this one has a few distinct advantages - it's among the cheapest on the market, it's available anytime, any day, and in addition to freshening breath, according to manufacturers, it helps fight gingivitis.

"I drink the big bottle every day," says McGlaulin, 55. He explains one recent night, while drinking on the steps of a church, that he steals it or panhandles to buy it. "I can't stand the taste, but it carries me over; it prevents the seizures."

In recent months, with more homeless on city streets, police say downtown convenience stores have seen a spate of thefts. The most stolen item: mouthwash. At $3.99 for a 50-ounce bottle, Listerine and similar brands pack a punch - with as much as 27 percent alcohol content, compared with about 12 percent for the typical bottle of wine. Another perk: drinking it is legal. Police can't arrest anyone for drinking mouthwash in public.

In response to the thefts and abuse, the owner of three 7-Eleven stores in the area decided to cut the number of brands he sells and keep the remaining bottles behind the counter. At the new Walgreen's on Summer Street, managers and clerks say they keep watch whenever people who are believed to be homeless enter the store.

And at several downtown CVS stores, signs next to the bottles of mouthwash read: "Selected products have been protected by the manufacturer against theft."

But the thirsty are rarely swayed from their objective. "They don't care - the signs don't mean anything to them," says Michelle Jimenez, a cashier at the CVS on Summer Street. "They either take a bottle and walk out, or they pay. We can't not sell it to them."

When the homeless walk into the 7-Eleven across the street, where the franchise owner estimates he has lost tens of thousands of dollars in thefts at his store this year, the clerks are told to try to dissuade them from buying mouthwash. "I say, `Try to steer the customer away,' " says J.R. D'Avila, the manager of the 7-Eleven on the corner of Arch Street. "The stuff's just not good for them."

However, health officials and outreach workers, who say they've seen a rise in the abuse of mouthwash by homeless alcoholics in recent years, argue it would be dangerous for stores to refuse to sell them mouthwash, especially on holidays or during the stretch between Saturday night and Monday morning when the state's liquor stores are closed.

Without a fix for too long, alcoholics suffer withdrawal - and some die from it. Studies of Boston's homeless population over the past decade have shown that more suffer seizures and die when they can't get a drink.

A study of 14 homeless people who died between 1998 and 1999 found nearly all died on Sunday or early Monday morning, according to Healthcare for the Homeless, the study's author. Three years earlier, a study of 1,700 emergency calls from shelters to police found that 25 percent of the calls were for seizures, with 75 percent of the calls on a Sunday or Monday.

"There's really a tough ethical dilemma," says Dr. James O'Connell, president of Healthcare for the Homeless, adding that mouthwash does not have any more severe medical consequences than other alcohol. "There are no easy answers. The real problem is alcoholism. But from a harm-reduction point of view, it's better to let them drink Listerine than to have a seizure," which can cause brain damage.

The best solution, O'Connell and others said, is to get the person into a detox facility or substance-abuse program. But with more drug and alcohol abusers on the streets, there aren't enough beds.